TMI

Too much information. That's the Digital Age for you.

In 1982 Buckminster "Bucky" Fuller (What a name!) rolled out his "knowledge-doubling curve." He proposed that the total knowledge available to mankind at any given time in history could be measured in units with the rate of increase determined. He estimated that the total amount of knowledge available at the time of Christ took 1500 years to double in scope. But in 250 years, in 1750, it doubled again, and then in just 150 years with further human innovation and advancement in science, the sum of human knowledge was eight times what it was in 0 A.D. (or in other words 8 "BC knowledge units"). With the advent of media and the internet in the 20th century, the amount of knowledge available to mankind accelerated further. According to Fuller's curve, in 1985 64 "BC knowledge units" were available.

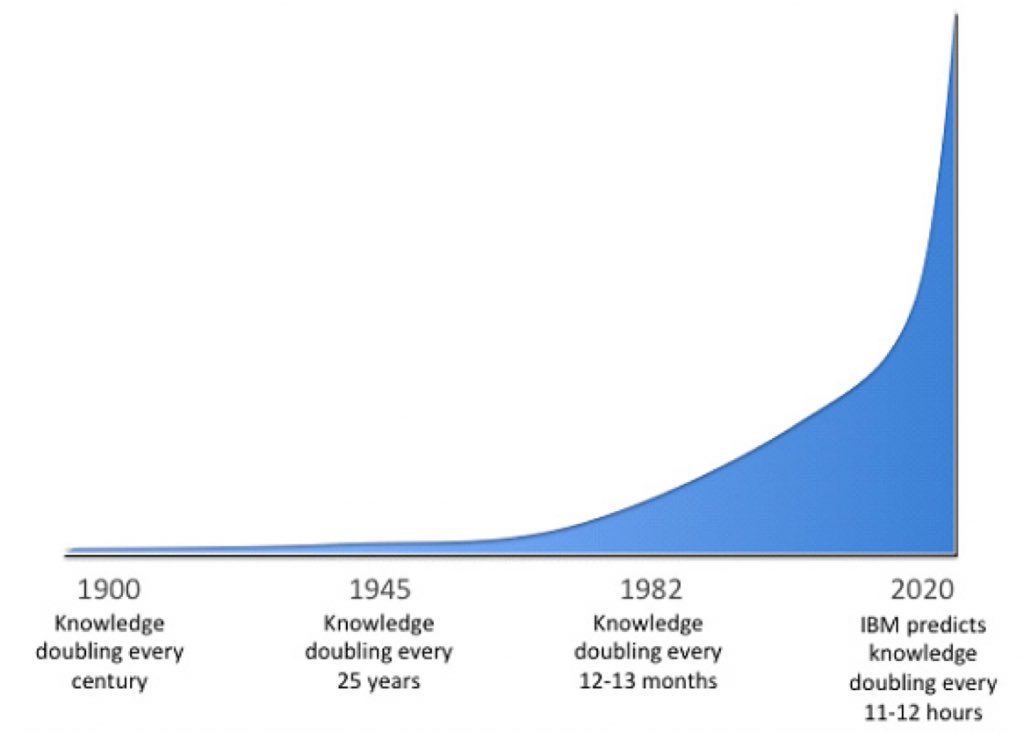

A way to see this concept in how long it takes the amount of knowledge to double is by graphing it. As the graph below shows, in 1900 the rate for information to double was every century; at the end of World War II it was doubling every 25 years: by 1982 the doubling rate was every year approximately, and currently it's on a pace to double every half day!

Here's yet another way to consider how this information is coming at us. The following statistics are worldwide ones. Google reports that they handle 3.8 million searches every minute. 8 trillion texts are sent every day. 350 million photos are placed on Facebook every day and 995 photos are shared on Instagram every second. 500 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every minute and over one billion hours of videos are watched every day.

All of this information tsunami washing over us is impacting us. As Nicholas Carr says in The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains:

What the Net does is shift the emphasis of our intelligence, away from what might be called a meditative or contemplative intelligence and more toward what might be called a utilitarian intelligence. The price of zipping among lots of bits of information is a loss of depth in our thinking.

How evident that is in public discourse these days. No one listens to others, thinks deeply, and responds graciously despite a difference of opinion anymore. Instead, people immediately vilify someone with whom they disagree.

As an example, a friend involved in politics reminded me recently of how quickly the media can pounce, even on "one of their own." After the Supreme Court Justice hearing for Amy Coney Barrett, Senator Diane Feinstein thanked her colleague Lindsey Graham for conducting the time as "one of the best set of hearings that I have participated in." She even gave him a hug. Cable news and other Democrats criticized her relentlessly for stepping over approved party lines. Before long, she was forced out of her role on the Judiciary Committee. As this difficult year has shown us, with all of the instantaneous information available and social media platforms people have, mobs form quickly.

TMI has innumerable other impacts. People have trouble determining what is true and false, as misinformation and rumors are spread at the speed of light. The great societal upheavals caused by the Corona virus are agitated even further by the incessant discussions about it on the internet. Studies show that the more people are on social media, the more depressed they are. Less than 60% of internet traffic is actually human, further depersonalizing us. Too many young people live vapidly, like the young college student I sat next to on a plane recently. Within moments of our introduction, I was told he had over 2 million TikTok followers and his identity was clearly rooted in it. The video specialty he showed me? Jumping in and out of superhero costumes.

Excellent guidance has been given by others on handling this information overload. Carr's The Shallows mentioned above helps the reader process this age in which we live. David Murray has written insightful articles on how to take a "Digital Detox." Likewise, Tim Challies has many articles such as "Parenting Well in a Digital World" and even offers the book The Next Story: Life and Faith After the Digital Explosion for assistance in this area. Use these resources to help you navigate the oceans of information before you.

But my purpose in writing this article, as I bring it to its conclusion, is singular in nature. I enjoyed a rich Lord's Day yesterday resting in God's presence and being reminded of His control over all things. It was greatly refreshing. I reflected on how that corresponded to the fact that I had been away that day from my computer, TV, phone, iPad, etc.

I also remembered how - because it is one of God's incommunicable attributes - that I cannot be omniscient. He and He alone is all-knowing.

Thus says the Lord, the King of Israel and his Redeemer, the Lord of hosts: “I am the first and I am the last; besides me there is no god. Who is like me? Let him proclaim it. Let him declare and set it before me, since I appointed an ancient people. Let them declare what is to come, and what will happen. Fear not, nor be afraid; have I not told you from of old and declared it? And you are my witnesses! Is there a God besides me? There is no Rock; I know not any” (Isaiah 44:6-8).

I cannot know, and consequently do not need to know, everything. But I do know the One who does. "The eyes of the LORD are in every place, keeping watch on the evil and the good” (Proverbs 15:3). Satisfaction in that truth tames the soul, taking away the vain thirsts to know so many other things. And it gives place to a deeper, eternal longing for a knowledge so vast that we have to pray for the Spirit's help like Paul did, so that we "may be able to comprehend with all the saints what is the width and length and height and depth, and to know the love of Christ which surpasses knowledge, that you may be filled to all the fullness of God" (Ephesians 3:14-19).

That is a "TMI" of a whole new dimension.