100 Years of Reformed Presbyterian Missions in Syria (Part 2 of 2)

This is part 2 of a 2-part series on the RPCNA mission to Syria, from 1856 to 1958. Part 1 provided an historical overview of the mission. Part 2 will analyze and evaluate the missiological methods employed.

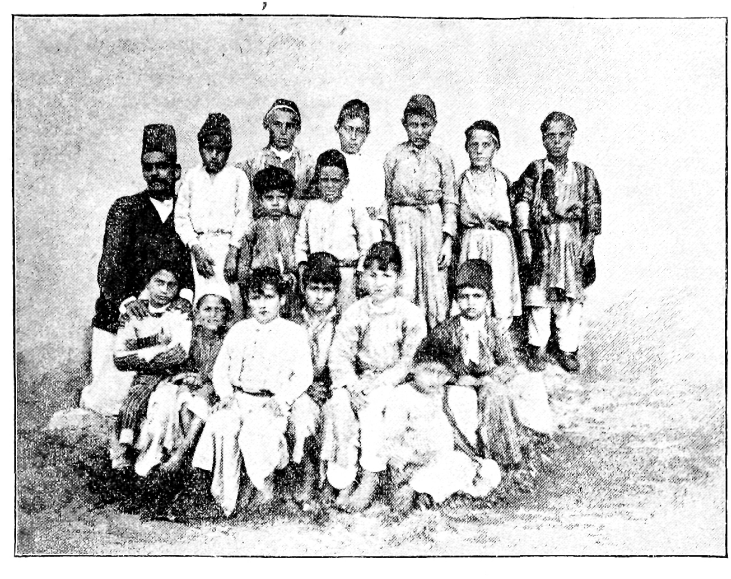

Note: The picture above is from page 33 of the Herald of Christian Missions (1894). The prior page states, "Through the kindness of Miss Meta Cunningham, we were able to present our readers with the accompanying picture of the boys in the Suadia school."

Before the Covenanter missionaries left Syria, they had already been considering how best to turn the work over to the national church.[1] In some ways, then, the mission had achieved its aims.[2] The goal was never a perpetual mission, but a self-sufficient church. Pioneer missionary Robert Dodds wrote that “The precise object of a foreign mission … is to plant the church of Christ in the designated field, and watch over her development and growth … till she has attained such a maturity as to be able … to maintain, perpetuate and extend herself.”[3] We will now examine the methods used by the missionaries, and how well those methods contributed to their purpose.

Language Learning

From the very beginning, the Covenanter mission stressed the importance of language learning. This was by necessity, to communicate. Nevertheless, the missionaries desired not just the ability to communicate, but rather a mastery of the language. Robert Dodds, for example, learned not just formal Arabic used for preaching and writing, but also the colloquial dialect used in conversation.[4] No further mention is made of the existence of such a diglossia, but it is assumed that missionaries continued to learn both the formal and informal registers of Arabic.

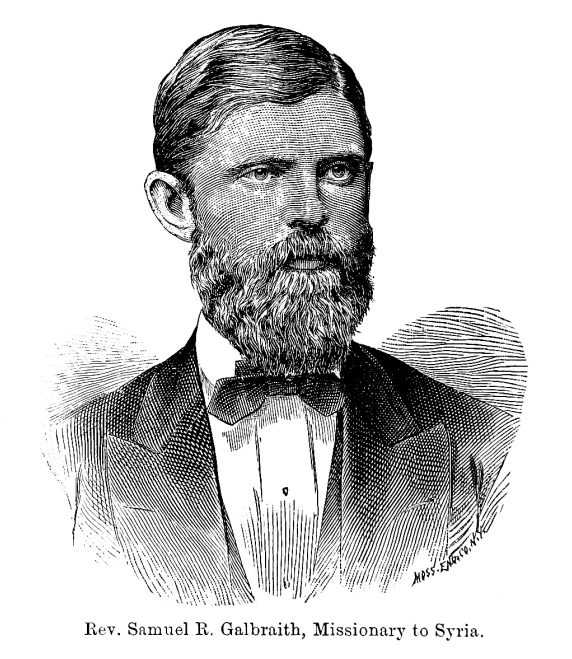

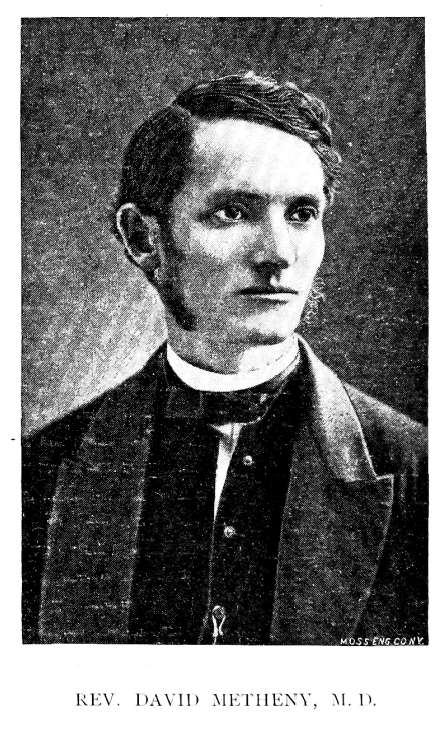

To learn Arabic, incoming missionaries dedicated about two years to language learning.[5] After an uncommonly cold winter leading to many deaths, an overwhelmed Dr. Metheny, the first medical doctor to join the R.P. mission, wrote: “I am very anxious that the church may send out a young man who is well-educated and a good physician. I say young, because much time is necessary to study this language.”[6] Nevertheless, even younger missionaries had to learn to take care of their bodies. Samuel Galbraith serves as a warning: “Reverend Galbraith's career was shortlived: possessed with an intense desire to master Arabic, he refused to give his body rest. He became ill with tuberculosis, and though ordered to a resort in the Lebanon mountains, he died, after a few days rest, at 28 years of age.”[7]

Preaching and Teaching

Having learned the language, the pioneer missionaries began their missionary work by preaching and teaching:

As both the officially appointed missionaries were ordained ministers it is not surprising to find them putting preaching the gospel in the first line of their attack on the powers of darkness.

And being Protestant preachers it is also no surprise to find them adding at the very beginning teaching as the second line. For their Commission read: “Preach the Gospel–teaching them.”[8]

Formal Lord’s Day preaching began on December 11th, 1859, in the missionaries’ rented home, three years after they first arrived. It was conducted in Arabic, “although only the missionaries and a servant formed the congregation.”[9] From then on, preaching continued every Sabbath with few exceptions.

In addition to preaching, “much time was spent in visiting the country villages, in getting acquainted with the people, and in doing other preparatory work that is always necessary in the opening up of a new field.”[10] Recurring mention is made of so-called “Bible readings.” Sanderson gives this account from around the turn of the century:

House to house evangelistic services were conducted by the Suadia missionaries and many of the converts. In one year, the Bible readers reported having read the Bible with 2,735 persons. The readers travelled in wet weather and dry. Miss Cunningham writes of going out with her Bible woman to make calls in a heavy rain. As they crossed a rapidly rising river and crawled up a steep bank on the other side, the Bible woman began to slip back toward the river. Failing to grab any shrubbery, she leaned back on Miss Cunningham. Below, the river rose higher while the rains drenched them from above. Spying a stout branch jutting out just above them, Miss Cunningham made a grab for it, and pulled herself and the woman up to the top of the bank. Covered with mud, the women returned, giving thanks to God for their safety.[11]

Evidently, the missionaries went on circuits throughout the villages, where they would be invited into homes and read Scripture. They appear to have done this quite openly, as heralds of the King.[12] This confidence seems to be a part of the Covenanter DNA, and it would be interesting to analyze the impact of the Reformed Presbyterian emphasis on “public profession, otherwise called covenanting” on missions in closed countries.[13]

What these Bible readings might have looked like may be seen in the translated reports of Syrian evangelists, which also serves to show the maturity of the indigenous Christian workers.

May 11. We went to the village of Rasgen and entered the house of the sheikh. After the usual salutations of peace, we began a talk founded on Matt. 5:37. The sheikh listened with apparent acceptance for some time and then went out to his work. After a while others came in and we read Matt. 5th chap., making remarks on different parts of it. They said, your words are true and we are all sinners. In reply to one who inquired, “Are not the saints and prophets worthy of honor and worship, and are they not mediators between God and man?” we read Ezek. 14:12-21, showing that Noah, Daniel and Job had no power to save others. We showed them that there is no way of salvation except by the one Redeemer Jesus Christ. As we were leaving, sheikh Hassen said, “Come again and read to us from God’s Word, for it is profitable for us to hear it.”

May 12. We went to Raseen, a Nusairiyeh village. We read Matt. 24 and 25 and spoke about the last day and Christ as the Judge, and that all would be judged according to their works. We spoke of the shortness of man’s days upon the earth, and the duty of preparation and watching, because we know not the day nor the hour when we will be called to give an account. These people were simple and unlearned. They did not ask many questions, but confessed that our words were true.–Report of teachers Yusef Aboud and Sucker Martin.

….

June 8. We came to El Dawer, and here we met some reapers and others sowing seed. We said to them, the time in which we shall see the King of kings gathering his wheat is near. Shall we be gathered into the garner, or cast out for the fire? The harvest field of the King of kings is the world, and he will gather everyone that fears him and believes in him, and take them to the place where he is; but the wicked he will cast into the pit of hell to suffer everlasting pains. They said, “Woe be to us, for we have never attended to these things, but to the things of the world.”

June 14. We went to Shemis. Our subject was the crucifixion of Christ. We asked them if they believed what was written in the Old and New Testaments. They said, “yes.” Then we said, “The germ of the gospel was, that Christ died on the cross, and that to redeem us from the curse of the law.” They replied, “Can it be possible that the Most High should suffer pain or be crucified?” We said, “no; the pain and suffering did not come on the Divinity but upon the humanity of Christ.” On this subject we had many words….– Report of teachers Maree Sayaight and Isa Ismiell[14]

From these accounts it appears that Bible readings were deliberate, direct, and Gospel-focused. Some were planned, while others took inspiration from the surroundings. The evangelists were also willing and able to answer sincere Muslim objections such as how the suffering of Christ could be reconciled with the impassibility of God.

Medical Missions

After preaching and teaching, the next “line of attack” was medical missions. McFarland continues his quote from the previous section: “And being human and remembering the example of their Master it is very natural to find them in a very few months urging the Board to send them a physician to make healing their third line.”[15] This was important for the safety of the missionaries,[16] the well-being of the Syrians, and as an opportunity to share the Gospel. Dr. Methany also continues his previously quoted remarks with an observation of the evangelistic advantages of a medical doctor:

I am very anxious that the church may send out a young man who is well-educated and a good physician … The people have great reverence for physicians and in their homes he can freely tell the Good News. He has extensive opportunities for he is frequently called to all classes. Many, many people now wish to be Protestants and Brother Beattie is rather employed in keeping them out, than in letting them in, as we know their motives are not good. Yet it is a pleasure to have even hypocrites thus testifying to the importance of religion.[17]

Education

Another major focus of the Syrian mission was education, a focus which began shortly after the beginning of the mission. In 1860, a school for boys was opened,[18] and in the same year the missionaries petitioned the board for a school for girls, which was built in 1866.[19] In addition to the mission station schools, many village schools were opened and run by native converts.[20]

Throughout the Syrian mission these schools tend to almost dominate much of the discussion. McFarland, reflecting on the first eight decades of the Syrian mission, saw schools (and especially boarding schools) as a particularly effective evangelistic strategy:

Every missionary who has had experience in conducting both boarding and day schools, testifies to the vastly superior satisfaction they found in the influence of the boarding school…. In these boarding schools a real Christian home was provided for them. Every pupil in them had to read and study the Bible every day, besides committing large numbers of Bible verses and the catechism…. They had morning and evening worship with a blessing at their meals. They were kept under wholesome discipline twenty-four hours a day. They went to Church and Sabbath School and the mid-week prayer meeting regularly. Even their play as well as their study outside of school hours was supervised by competent Christian teachers. No wonder even prominent Moslems said: “We like your schools for their influence on the morals of our children.” We are convinced that more spiritual dynamite has been planted in the social structure of Syria by these Christian boarding schools than by any other one method. “My Word shall not return unto me void,” saith the Lord.[21]

While effective, the schools also proved to be a liability as the missionaries were forced to navigate the complexities of changing politics and multiple wars. For example, in 1952 new laws were passed which forbid non-Christians from attending Bible classes, and also forbid schools from being restricted to Christians.[22] This growing pressure forced the mission to figure out how to make the schools self-supporting so that control of the schools could finally be given over to an indigenous Board of Directors in 1957.[23] Another drawback of the school model was that established schools required an outsized share of resources, and also “siphoned off virtually all of the eligible ministerial candidates,” thus slowing the growth of the institutional church.[24] Despite these difficulties, the Christian school answered a need for Christian education which has always been a Covenanter emphasis.

Church Organization

The work of the church continued slowly in the background. By 1872, James Beattie had seen enough fruit that he decided to start a seminary to train Syrian pastors and evangelists.[25]Native ministers and evangelists were formally licensed by the church for the work of ministry. In addition, there was also the creation of an indigenous Missionary Society of the Syrians, composed of native men and women.[26]Although many Syrians were licensed to preach, after twenty-six years there were still no ordained Syrian elders and deacons. Therefore, the Foreign Mission Board sent a delegation to investigate in 1888, resulting in five ruling elders and four deacons ordained by 1890.[27] Even then, the first Syrian pastor was not ordained until 1921.[28]

Attempts were also made to organize the churches into a Syrian Presbytery. A Syria Presbytery of three churches was briefly organized in 1895,[29] but was disorganized a year later for failure to meet.[30] At Synod in 1936, the Board of Foreign Missions recommended a joint Syrian Presbytery with the Scotch-Irish,[31] although no such Presbytery was ever formed.[32] It was not until 1961, three years after the Syrian mission ended, that the remaining two congregations joined the National Evangelical Synod of Syria and Lebanon.[33] The church in Latakia, now the National Evangelical Presbyterian Church of Latakia, continues to meet and is one of the largest churches in Latakia with a capacity of 400 and a membership of 1000.[34]

Relation to the Government

One final note of interest pertains to the posture of the Covenanter missionaries to an often hostile government. Generally, they respected the legitimacy of the government and were not afraid to appeal to it for protection.[35] However, when the same government became the persecutor, then, according to Balph, “the descendants of the Covenanters, who defied a hostile government in Scotland to obey God, were only stiffened in their determination by such opposition and the work went on.”[36] This opposition ranged from covert to overt, as wisdom called for. After World War I, for example, the government made reentry difficult for the missionaries, who were forced to return “under the auspices of the Near East Relief.”[37] Other times, the opposition was direct, as when Herbert Hays was confronted by the Chief of Police regarding the charge of evangelizing Muslims, which was strictly forbidden:

He [the Chief of Police] queried, “We realize you teach people to have good characters and life [sic] a better life. But, do you evangelize the Moslems?” “Yes, if they want to listen,” replied Mr. Hays. With that he handed the policeman a New Testament and a book about the Apostle Paul, and continued: “Our Master told us, ‘Go ye into the world and teach the gospel,’ and that includes the Moslems. Will you not read these books and see if you can find anything wrong in them?”[38]

Conclusion

As the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America contemplates future mission fields in Muslim-majority nations, what lessons can be learned from the Syria mission? The original goal of church planting must continue to be the aim of missions. To do this, language learning and long-term missions are vital. Priority must be given to raising up local ministers to be the future leaders of the church. Education should be seen, not as an evangelistic strategy, but as a component of the discipleship of covenant children, in whatever form makes the most sense. The Syrian mission, although not perfect, is a testimony of God’s faithfulness to those who “did not love their lives to the death” (Rev. 12:11).

[1] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 98.

[2] The missionaries’ last words as they sailed away from Latakia were a tearful, “Mission accomplished.” Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 107.

[3] David Mellville Carson, A History of the Reformed Presbyterian Church in America to 1871 ([Philadelphia]: Carson, 1964), 205.

[4] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 2.

[5] In some cases, language learning took as long as three years. McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 66. See also page 77.

[6] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 11-12.

[7] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 14.

[8] McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 12.

[9] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 3.

[10] Balph, Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria, 38.

[11] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 42.

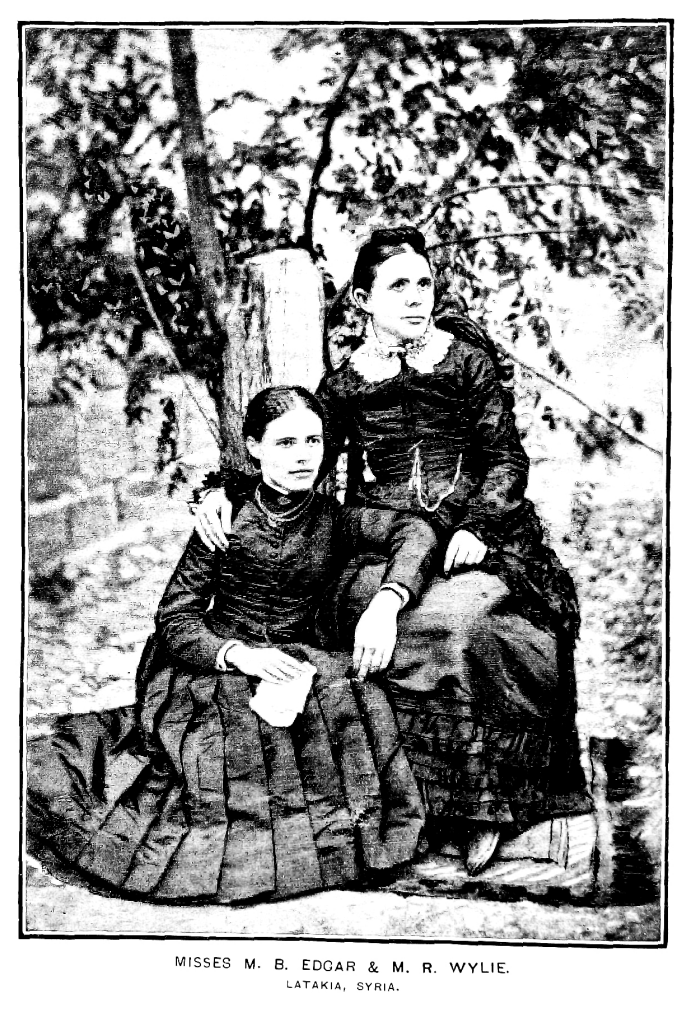

[12]This confident witnessing seems to be a part of the Covenanter DNA. The risks were very real–Maggie Edgar, the only Covenanter martyr in Syria, was probably stabbed and dumped into a river during a home visit. McFarland writes, “There is plenty of circumstantial evidence to indicate that she was foully murdered by the man of the house where she made her last visit, and near which she was last seen in the flesh. The man is known to have other blood on his soul. It is ‘whispered’ that a woman of the family cried out as Miss Edgar entered that day: ‘Oh Miss Edgar, why did you come now? My brother will kill you.’” McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 73.

[13] Vow 3 of the Queries for Ordination, Installation, and Licensure. RPCNA, The Constitution of the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America(Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Crown and Covenant, 2018), G-2.

[14] R. M. Sommerville, editor, Herald of Mission News (New York: N.P., 1887), [3] in “Items of Missionary Intelligence.”

[15] McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 12.

[16] “Before a medical doctor could be supplied to the Syrian Mission, the missionaries suffered the loss of many of their children.” Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 6.

[17] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 11-12. The value of a medical doctor was proven early in the mission after the Greek Orthodox bishop forced the closure of the missionary schools by pronounced a sentence of excommunication on anyone who talked to a Protestant. However, “Soon the priests, and then the Bishop took sick, and were forced to seek help from the only person who could cure them, Dr. Metheny. When the Bishop announced to the Greek Orthodox that in case of emergencies they should seek the help of a Protestant, ‘emergencies’ of an unprecedented number arose!” Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 7.

[18] Balph, Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria, 26. See also Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 3.

[19] Balph, Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria, 38. The school for girls was noteworthy in an Alawite context which devalued women. R. P. missionary Rebecca Crawford wrote, “These mountain people consider it a curious experiment that we try to educate girls. They constantly ask, ‘Can they learn anything?’” Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 8.

[20] Balph, Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria, 43.

[21] McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 45-46.

[22] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 96-97.

[23] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 101, 103.

[24] Abdulfadi, Basheer [Pseudonym], “The Missiology of the R.P. Mission to Syria,” Semper Reformanda 11 (2002): [78-79].

[25] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 14.

[26] McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 30.

[27] Edgar, Founding Churches in Ottoman Empire Territory.

[28] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 80.

[29] RPCNA, Minutes of the Synod of the Reformed Presbyterian Church of N.A. (New York: Pratt & Son, 1896), 37.

[30] Balph, Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria, 101. See also McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 44. It seems that Henry Easson and James Stewart refused to attend because “the Presbytery’s powers and sphere had not been stated” and they worried about a scenario in which “a native member could drag them at pleasure for any and every fancied grievance.” RPCNA, Minutes of the Synod of the Reformed Presbyterian Church of N.A. (Walton: N.P., 1898),121

[31] RPCNA, Minutes of the Synod of the Reformed Presbyterian Church of N.A. (Pittsburgh: N.P., 1936), 10.

[32] Edgar, Founding Churches in Ottoman Empire Territory.

[33] Edgar, Founding Churches in Ottoman Empire Territory. The NESSL is broadly Reformed and Presbyterian, descended from the PC(USA) but now an independent entity. See http://synod-sl.org/history/. Accessed April 2021.

[34] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Evangelical_Presbyterian_Church_of_Latakia. Accessed April 2021.

[35]For example, after being ejected from Zahle, the missionaries’ first response was to appeal to the government, which proved fruitless. Balph, Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria, 22. Roughly 50 years later, appeals to the government were still being made, which resulted in Protestant Christians securing government recognition in Suadea. Balph, Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria, 119.

[36] Balph, Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria, 38.

[37] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 71. Though, as McFarland notes, “their main work was relief for some time.” McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 65.

[38] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 102-103.