The Massive Value of Unpaid Work

Dan Doriani begins his 2019 book Work with a critical insight: the market economies we live in devalue work that doesn’t pay.

This is why, he says, it’s so hard for stay-at-home mothers, retirees and others to feel their work has significance.

My wife can relate. When I come home she’s eager to hear about my work—even the headaches—because I’m often the first adult she’s talked to all day. She’s worn out by her work—washing clothes, fixing meals, picking up after our kids—and by seeing it undone almost as soon as it’s done.

Stay-at-home moms can find hope in the long-term impact their work has on the hearts and minds of their children, but their surrounding culture—far more interested in material gains and visible progress—won’t do much to nurture that hope.

Our culture regards the material as more significant—in fact, more real—than the non-material. This isn’t a new development. Richard Weaver, in his book Ideas Have Consequences, traced the problem to a philosophical shift in the late Middle Ages, which declared that words and ideas actually did not correspond to universal, transcendent truths.

Over the following centuries, this shift produced a series of other changes that gradually replaced a cultural belief in universals—like God and goodness, beauty and truth, soul and spirit—with a cultural belief only in material things that can be perceived by our senses and sensory tools, like MRI machines. Weaver wrote, “Man created in the divine image, the protagonist of a great drama in which his soul was at stake, was replaced by man the wealth-seeking and -consuming animal.” This second story is still the one our culture tells us every day.

However, there is encouraging progress coming lately from an unlikely source: economists.

Among economists, there is a growing body of work that has shown that individuals who do not usually directly participate in formal labor markets, contribute informal labor by performing household services, volunteering, babysitting, counseling, mentoring and other activities.

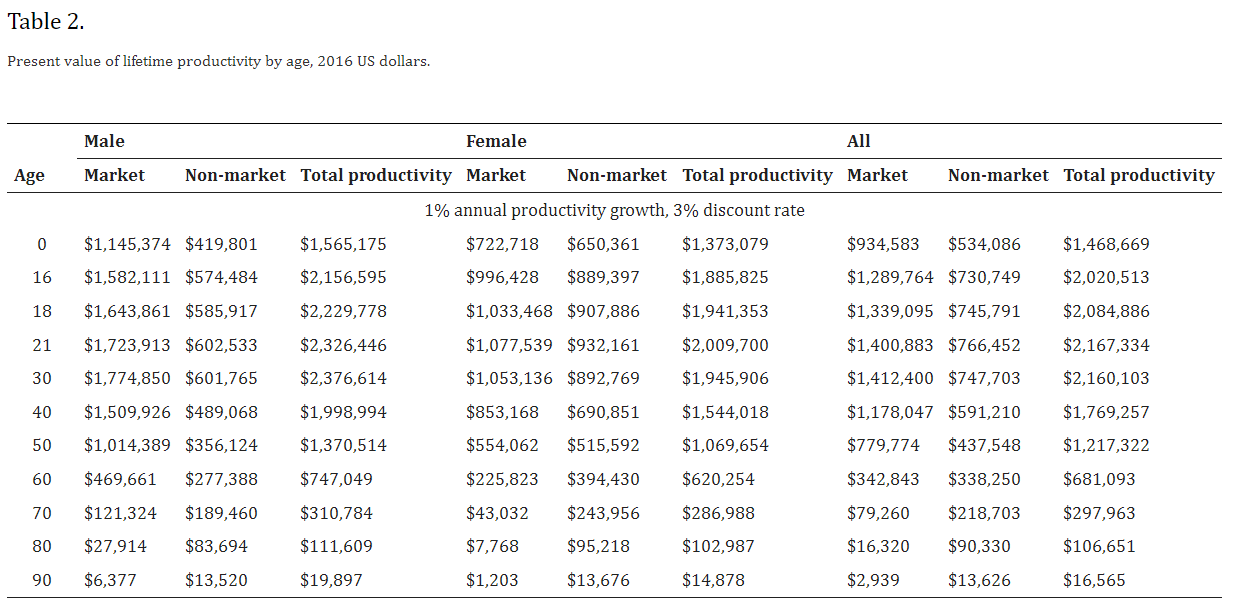

Scott Grosse, an economist at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, has published multiple studies calculating the value of both “market productivity” and “non-market productivity.” His latest estimates, published in 2019, show that the average person born today will over his or her lifetime, contribute $1.5 million in productive labor—and 57% of that will be unpaid.

As you can see in the table below, women on average contribute more “non-market” labor than men—yet their lifetime contributions are roughly the same overall. You can see that retirees' productivity does go down compared with their pre-retirement years—yet their productivity never hits zero.

In short, every person, at every age, is contributing productive labor that should be valued by our society.

The main reason Grosse and other economists want to put a number on unpaid labor is to enable better evaluations of the burden of illnesses. For example, cancer isn’t just life threatening for the people it afflicts, it also reduces their ability to work—in both paid and unpaid jobs. It may also require one of their family members to reduce their work, both paid and unpaid.

Knowing how much productivity is lost due to an illness is critical to fully evaluate the value of a new treatment for that disease. If a new medicine were to cure cancer, its benefits should not only be calculated in extra years of life or better quality of life, but also in the additional productivity—both paid and unpaid—enabled by removing the burden of the cancer.

Since governments and private health insurers often pay most of the cost of health care, they want to know whether the price of a new medicine or new surgery is worth it. And they need to know the full impact on productivity—both paid and unpaid—to make such decisions.

The work of these economists add evidence to what we as Christians already know: that the most valuable things we do are unpaid. We live in the faith that by devoting ourselves to relationships—with God and with each other—God is using our labor to produce things of inestimable value. When we take a sabbath rest to worship, when we pray, when we take time for devotions and fellowship, that is the most valuable time we spend each day and each week. When parents make regular time for their kids, and grandparents for their grandkids, that is the most productive work they can do.

But, if you’re like me, it also helps once in a while when someone puts a dollar figure on it and tells us, yes indeed, all that unpaid labor is of massive value.

"Stay-at-home parents and volunteers do essential work, whether paid or not," Doriani wrote. "We should honor work that meets needs and promotes justice and mercy."