Textual Confidence

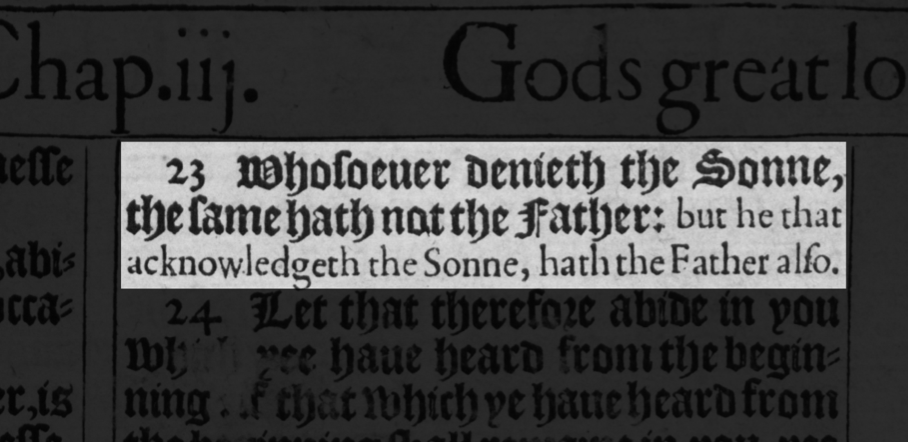

Has God’s word been deliberately tampered with over the years? Have verses teaching the deity of Christ been systematically removed from our Bibles? Are the differences between ancient, modern and Reformation-era Bibles so significant that some of us have completely different Bibles from our fellow church members? Does admitting uncertainty about any part of the Biblical text (as the KJV translators did in their footnotes), mean that we can’t be certain about any of it?

You may have heard such claims. In fact, you may have heard them from two opposite ends of the spectrum. You may have heard them from liberals and sceptics such as Bart Ehrman, or you may have heard them from some in the church who could never in a million years be confused with a theological liberal.

Either way, it leads to the same result. It leads to the confidence of God’s people in their Bibles being shaken. And that is an unspeakable tragedy.

We could call the first group ‘textual sceptics’. They believe that the Bible is so hopelessly corrupted that there’s no way we can have any certainty about what it originally said.

The second group are ‘textual absolutists’. They hold up one particular form of the Biblical text as having absolute authority over against all other forms of the text. This can either be a translation (like the Latin Vulgate) or certain printed Greek texts (like the Reformation-era Greek editions which mostly lie behind the King James Version). Whatever form the absolute authority takes – whether printed text or translation – it is seen as beyond revision, even if clear errors have crept in somewhere along the way. (And even though everything set up as an absolute authority is itself a result of revision).

Such is the absolutist’s commitment to their preferred form of the text, that to admit any doubt here would be tantamount to giving up all confidence that the Bible is the Word of God. Such a position is not new: the KJV translators knew of some in their own day who did not want marginal notes in their Bibles ‘lest the authority of the Scriptures for deciding of controversies, by that show of uncertainty, should somewhat be shaken’.

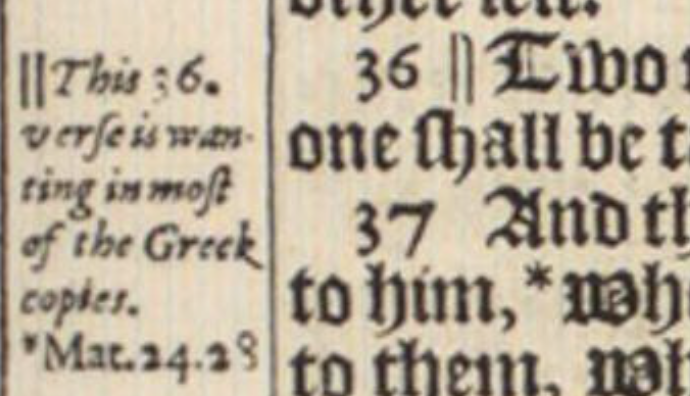

But there is a third way: textual confidence. This is a position shared by the Reformers, the editors of those Reformation-era printed Greek texts and the KJV translators themselves. Textual confidence means the ability to admit uncertainty in places without losing confidence in the Bible as a whole. As the KJV translators put it: ‘It is better to make doubt of those things which are secret, than to strive about those things that are uncertain’. In fact, they said that ‘to dogmatize…of such things as the Spirit of God hath left questionable, can be no less than presumption’. Rather, ‘they that are wise had rather have their judgments at liberty in differences of readings, than to be captivated to one, when it may be the other’.

But does admitting uncertainty in places mean that we must throw out our Bibles? By no means! As the Westminster Divine Samuel Rutherford put it, even though errors may have been introduced in the copying or printing of Scripture, ‘we yet hold providence watches so over it, that in the body of articles of faith, and necessary truths, we are certain with the certainty of faith, it is that same very word of God’. [1]

Recently, four very gifted and charitable brothers sat down to discuss the history and practice of textual confidence, over against textual absolutism. Of the four, one is a world expert in the history of the King James Bible, and another preaches from it each week. A third began a recent book with a chapter entitled ‘What we lose as the Church Stops using the KJV’. A hatchet job on any particular translation this is not. Rather, they want to see the principles of the KJV translators understood and applied in our own day. The result of their collaboration is seven hour-long YouTube videos, which are worth the time of anyone with even a passing interest in these issues – and particularly any who are finding their churches troubled by them.

All four of members of the ‘Textual Confidence Collective’ were brought up in textual absolutist churches, but came to see that many of the things they had been taught did not add up, or were simply untrue (even if those teaching them truly believed them). By God’s grace none of them walked away from the faith, but that is undoubtedly one of the things at risk if we go wrong here. A false absolutism actually militates against true confidence.

Like the KJV translators, these brothers have faced an inordinate amount of ‘bitter censures and uncharitable imputations’ – some from their own families. However the videos they have produced are a gift to the church, and well worth whatever ‘storm of gainsaying or opposition’ will come their way.

You can watch the first one below: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mseAF_n40xk

[1] Samuel Rutherford, A free disputation against pretended liberty of conscience (London, 1649), pp 366.