Resurrection Sunday

Christians have always accorded special significance to the first day of the week. We worship corporately on Sunday because it was the day on which Jesus rose from the dead. Well aware that the time of the resurrection gives us a significant directive as to when and how we ought to worship, some who insist on retaining the Old Covenant day of worship—the seventh day Sabbath—defend the theory that Jesus rose from the dead on Saturday. What follows is a defense of the traditional Sunday resurrection view, against the Saturday position as argued by Richard T. Ritenbaugh. As we will see, the Saturday resurrection view (a) fails to live up to the rigid timeframes that it erects; (b) cannot make sense of many details of the Gospel narratives; and (c) deprivtion; (b) is naturally derivable from all four Gospel narratives taken individually, and together; and (c) fills the resurrection with multiple typological connections.

The First Day (Sunday) Resurrection View

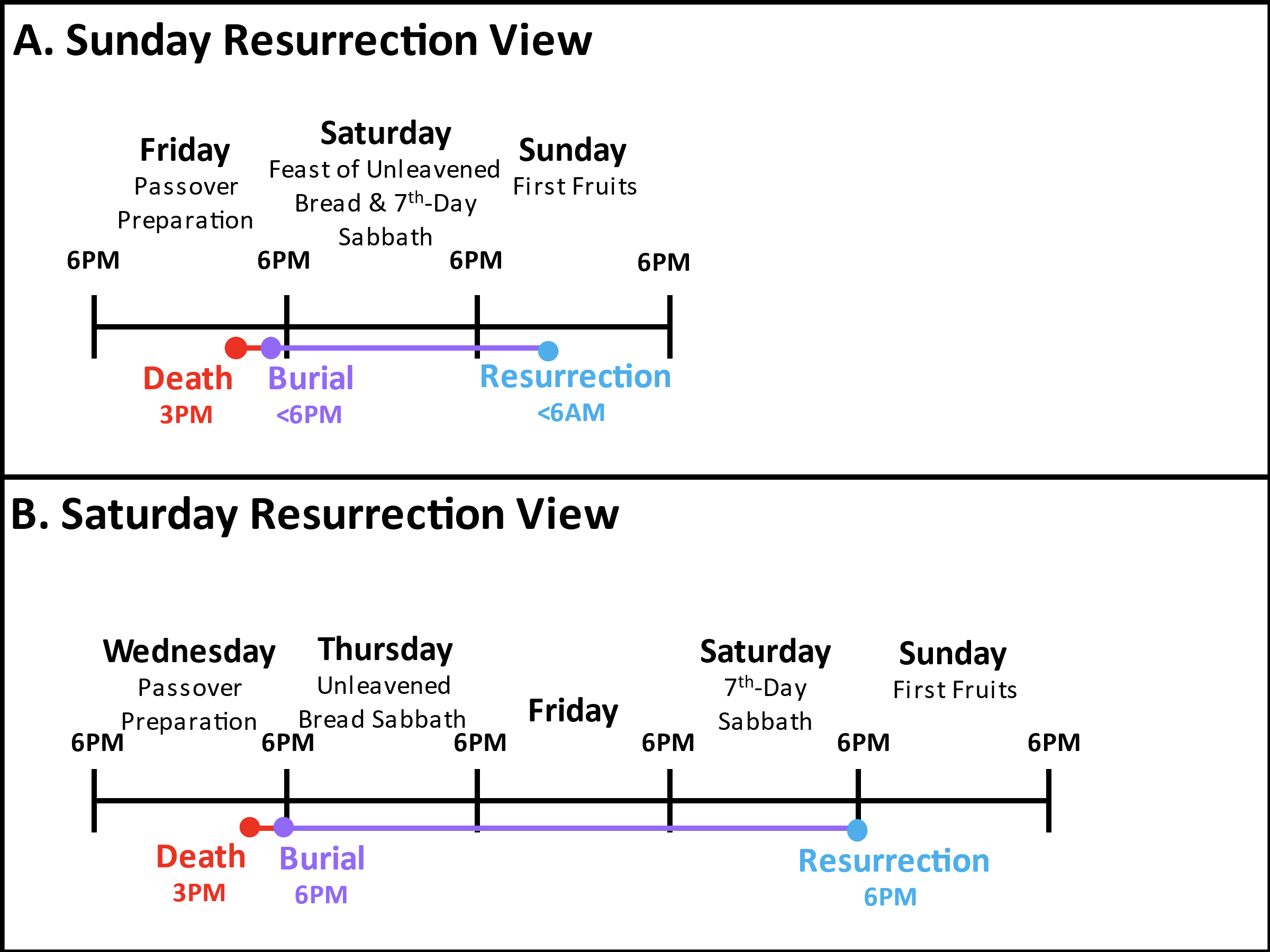

Christians have long understood Jesus to have been crucified on a Friday, and to have died at the “ninth hour,” or roughly 3:00 PM of the same day (Matt. 27:46; Mark 15:33-34; Luke 27:44-46). The time of day is evident on account of the following considerations. On the prominent Jewish reckoning (see Gen. 1:5; Lev. 23:32), the first half of the day is nighttime, beginning at sundown, or roughly 6:00 PM. And, the second half is daytime, beginning at sunrise, or roughly 6:00 AM. Hence, the “ninth hour” of the daytime is 3:00 PM, since the hours are calibrated from sunrise (around 6:00 AM). It is natural to conclude that the crucifixion occurred on a Friday from the fact that it is described as the “preparation day” (Mark 15:42; Luke 23:54; John 19:42; cf. Matt. 27:62). When God rained manna down from heaven following the exodus, He only did so for the first six days of the week so that His people would not engage in the labor of gathering on the seventh day. Thus, the Israelites were to gather twice as much on the sixth day, in preparation for a distinct rest on the Sabbath. The Jewish people in Jesus’ day not only called the sixth day “the day of preparation,” but had been granted a special freedom to tend to that preparation by Caesar Augustus (Josephus, The Antiquity of the Jews, 16:6:2). However, Jesus’ crucifixion not only occurred on the sixth day of the week, but on Friday, Nisan 14; the appointed time for preparing and slaying the Passover Lamb (Ex. 12:6, 18; Lev. 23:5-6; Num. 9:2-5; 28:16; Josh 5:10) for consumption at the beginning for the Feast of Unleavened Bread in the evening (which on the Jewish reckoning is the beginning of Nisan 15). Thus, in the year of Jesus’ death, the Sabbath Feast of Unleavened Bread which began on Nissan 15 (Lev. 23:6; Num. 28:17; Josh. 5:11) coincided with the weekly Sabbath. John calls the Saturday Sabbath following Jesus’ death a “great” or “special” day, apparently on account of this overlap of two holy days upon it (John 19:31; cf. 19:14).1 As for the timing of His burial, Jesus must have been entombed sometime before 6:00 PM on Friday. It was illegal to do the work of burial any later, since labor of this kind was prohibited on the Sabbath (which began at Sundown). The Law also stipulated that a crucified body must be buried on the same day as the execution took place (John 19:31; cf. Deut. 21:23; Josh. 8:29; 10:26-27). Finally, Jesus must have risen early in the morning (before 6:00 AM) on Sunday. Multiple Scriptures testify that Jesus rose from the dead “on the third day” after His crucifixion (Matt. 16:21; Luke 18:33; 24:7, 21; 46; John 2:19; Acts 10:40; 1 Cor. 15:3-4), which would be a Sunday (Friday, Saturday, Sunday). Furthermore, each Gospel reports that the disciples went to Jesus’ tomb and found it empty on the “first day of the week” (Matt. 28:1; Mark 16:1-2; 24:1; John 20:1), “while it was still dark” (John 20:1).

The Seventh Day (Saturday) Resurrection View

Despite the longstanding and widespread agreement among Christians that Jesus rose from the dead on Sunday, Richard T. Ritenbaugh believes that the traditional position cannot be reconciled with the words of Jesus in Matthew 12:40—“Just as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the sea monster, so will the Son of Man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth.” Allegedly, the phrase “three days and three nights” must denote a full 72-hour period, since Jesus once defined a half-day as 12 hours (John 11:9). Yet, according to the Sunday resurrection view, Jesus would have only been in the tomb for roughly 36 hours (from around perhaps 5:00 PM Friday, to perhaps 5:00 AM Sunday). Hence, Ritenbaugh offers an alternative scheme, which hinges on the claim that the Sabbath Feast of Unleavened Bread and the weekly Sabbath fell on two different days; the former occurring on the Thursday in the week that Jesus was crucified, the latter on the following Saturday, with a Friday in between the two. In this case, Jesus’ death would have occurred on a Wednesday, which was the “day of preparation” before the evening Passover Sacrifice, and the Sabbath Feast of Unleavened Bread. Supposing that Jesus was entombed right at 6:00 PM, His body could have remained in the “heart of the earth” for a full 72 hours before He rose from the dead at the very end of the Saturday Sabbath, at 6:00 PM. On this scenario, it is natural that the disciples would have found Jesus’ tomb empty when they came to it on Sunday morning. For, Jesus had already been raised for some 12 hours! Allegedly, this scheme, and no other, is capable of satisfying all of the Biblical data. It is also taken as a strong proof that New Covenant Christians are still bound to Seventh Day worship.

The Meaning of "Three Days and Three Nights"

Before critically evaluating the details of the Saturday resurrection theory, we may begin by observing that the fundamental premise upon which it is based—that “three days and three nights” is a technical phrase denoting a 72-hour timeframe—is imperceptive of the regular use of such phrases in the Scriptures. In short, a phrase like “three days and three nights” could be used to denote a three-day timeframe within which certain events might take place, without exactly or completely spanning 72 hours. For example, Queen Esther directed the Jews to join her in fasting for three days—“do not eat or drink for three days, night or day”—prior to her consequential meeting with king Ahasuerus (Est. 4:16). And yet, the text tells us that “on the third day,” which would technically be premature of a fast that spanned three full days and three full nights, Esther met with the king (Est. 5:1). Genesis 42:17 indicates that Joseph had his brothers imprisoned “for three days.” Yet, Genesis 42:18ff indicates that Joseph had his brothers released at some point “on the third day,” prior to a full 72-hour imprisonment. Again, 2 Kings 22:1 states that “three years had passed without war between Aram and Israel.” And yet, the very next verse indicates that a full three years (1095 days) of peace must not have elapsed, because sometime “in the third year” (2 Kings 22:2) Israel and Judah resolved to go to war with Aram. This same use of language—where an event is described as occurring both after and within a three-day, three-month, or three-year timeframe—appears in 1 Sam. 30:12-13; 2 Chron. 10:5, 12; 1 Kings 20:29; and Luke 2:21. What all of this means is that according to the common parlance, passages which speak of Jesus as (a) remaining in the tomb for “three days and three nights” (Matt. 12:40), (b) rising from the dead on “the third day” (Matt. 16:21; Luke 24:21; 46; 1 Cor. 15:3-4; Acts 10:40; cf. John 2:19-21), or (c) as rising “after three days” (Mark 8:31; Matt. 27:64) may all be taken to mean that the events of Jesus’ death, burial, and resurrection occur within a three day timeframe. Once this is understood, there is no problem posed by the Sunday resurrection position that should send one searching for another view.

Despite all of this, the enthused advocate of a seventh day resurrection might respond that his position—that Jesus was in the tomb for exactly 72 hours from Thursday to Saturday—is, at the very least, a plausible construction of the death-burial-resurrection events. Moreover, it might be held that the Saturday resurrection view has as its distinct advantage the ability to allow “three days and three nights” to assume a 72-hour meaning. In truth, the seventh day resurrection theory cannot even be entertained as a plausible scheme for the pivotal Gospel events.

Failure to Solve the Alleged 72-Hour Problem

The most ironic feature of Ritenbaugh’s argument for a Saturday resurrection is that it fails to comport with the rigid timeframes that supposedly disallow the Sunday resurrection position. For, in addition to defining the length of Jesus’ stay in the tomb as “three days and three nights” (Matt. 12:40) which Ritenbaugh insists must denote a 72-hour period, the Scriptures also indicate that Jesus rose from the dead “on the third day” after His death (Matt. 16:21; Luke 24:21; 46; 1 Cor. 15:3-4; Acts 10:40). Mathematically speaking, it is strictly impossible for an event to span the entirety of three full days (72 hours), and to come to its terminus on “the third” of those three days.

Suppose, for example, that Jesus had, in fact, been entombed at the very moment of sundown (say exactly 6:00 PM) on what we would call Wednesday night. In this case, Jesus would have been buried, on the Jewish scheme, at the very beginning of Thursday. Then, if Jesus were in the tomb for a full 72 hours—the alleged meaning of “three days and three nights”—He would have risen from the dead at 6:00 PM on what we would call Saturday evening, but which would have marked the very beginning of Sunday on the Jewish reckoning. But in this case, Jesus would have been raised from the dead on the fourth day (Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday) after his burial (and the fifth day after his death), not the third. On the other hand, if Jesus were buried just before sundown (say exactly 5:59 PM) on Wednesday, then with 72 hours in the tomb, Jesus must have risen on Saturday at 5:59 PM. Note again, Saturday would have been the fourth day after His death and burial (Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday), and not the third day. This problem is exacerbated when we demand wooden precision for other timeframes that Jesus erected with respect to His death, burial, and resurrection. For example, speaking of His body Jesus prophesied, “destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up.” Taken strictly, the phrase “in three days” would mean “within” (but certainly not exceeding) a timespan of 72 hours from when His body was “destroyed” or killed. It is impossible that Jesus could have risen from the dead within 72 hours of when He was crucified, and that He should remain in the tomb for a full 72 after He was buried, because there is a three-hour disparity between these two events; Jesus having been killed at 3:00 PM and Jesus having been entombed at around 6:00 PM. Jesus would either have to have risen from the dead 72 hours after He was killed, which would be some 69 hours after He was entombed (3 hours short of the alleged 72 hour requirement), or He would need to rise from the dead 72 hours after He was entombed, which would be some 75 hours after He was killed (3 hours more than a 72-hour timeframe from when He was killed).

The point of this sort of number crunching is to demonstrate that Ritenbaugh and other Saturday resurrection advocates are mistaken in supposing that the phrase “three days and three nights” rigidly denotes a 72-hour period.

Three Days for Whom?

In order to evade the abovementioned sorts of difficulties, Ritenbaugh labors to prove that Jesus never predicted that he would rise from the dead on the third day from his crucifixion. Notably, he does not specifically make sense of John 2:19, Matthew 16:21, Luke 24:46 in this regard. However, his manner of handling a few select texts is altogether telling with respect to his capacity as a Bible interpreter. For example, in Matthew 27:62-64 the Pharisees approach Pilate on the day after Jesus was crucified in order to inform him of Jesus’ teaching that “after three days I am to rise again.” From this text, Ritenbaugh draws the cumbersome conclusion that the Pharisees misunderstood this Jesus-saying to mean that He would rise from the dead three days after the day after he was crucified; which happened to be the very day they were petitioning Pilate. Thus, they allegedly requested that Roman soldiers guard the tomb “until the third day,” not from Jesus’ death, but from the (supposed) Thursday on which they met with Pilate (making the “third day” in view the fourth day after Jesus had been buried). Of course, there is no detail in Matthew 27:62-64 which so much as hints that the Pharisees understood the commencement for counting Jesus’ “after three days” prophecy to commence on the day after His death/burial. It is the most natural, therefore, to suppose that the Pharisees understood Jesus’ words correctly, and were seeking Roman guards for the same timeframe explicitly described by Jesus in Matthew 16:21—“[I] must be killed, and be raised up on the third day.” Another oddity that arises from Ritenbaugh’s construction is that even if (against any natural reading of Matthew 27:62-64) the Pharisees’ request was for Roman soldiers to guard the tomb for three days, beginning on the day after Jesus was crucified, then we would have expected the guards to have left the tomb at the end of Saturday (Thursday, Friday, Saturday). And yet, the Gospel of Matthew implies that the guards did not leave until Sunday, which would have been a day longer than the Pilate agreed to station them at the tomb (Matt. 28:1-4). Hence, Ritenbaugh’s alteration in the chronology of Jesus’ death and resurrection both lacks warrant from contexts in which these events appear, and conflicts with other significant details of the Gospel narratives.

A second passage which Ritenbaugh labors, unsuccessfully, to reconcile with his position is Luke 24:18-22, where two men on the road to Emmaus encountered the risen Christ without realizing His true identity. They explained to the risen Lord that in the recent past, “the chief priests and our rulers delivered Him [Jesus] to the sentence of death, and crucified Him.” In fact, they report that “it is the third day since these things happened” (Luke 24:20-21). Strangely, Ritenbaugh advances the conclusion that the “things” since which it was the “third day” were not the trial and crucifixion mentioned one verse earlier, but the (rather uneventful) occasion on the day after the crucifixion, when the Pharisees allegedly requested that a Roman guard be stationed at the tomb. Of course, the Pharisee’s request to Pilate is not mentioned anywhere in Luke 24. In fact, it is not mentioned in the Gospel of Luke at all. Thus, a careful reading of Luke 24:20-21 in its own context leaves us with the inevitable conclusion that Jesus rose from the dead on a Sunday, the third day after His Friday crucifixion.

Seventh Day Resurrection Position Has No Foundation in Scripture

The awkward interpretations offered above call our attention to the fact that Ritenbaugh’s seventh day resurrection theory is far removed from the text of Scripture. One of the most significant problems with Ritenbaugh’s construction is that the reader of the Gospel accounts will only find three days of the week that are specifically mentioned with respect to the events in view—(a) The day of preparation on which Jesus was crucified, prior to the weekly Sabbath (Matt. 27:62; Mark 15:42; Luke 23:54; John 19:42); (b) The weekly Sabbath itself, during which Jesus was in the tomb (Matt. 27:62; Luke 23:56); and (c) the first day of the week (following the Sabbath) when Jesus’ tomb was found empty (Matt. 28:1; Mark 16:1-2; Luke 24:1; John 20:1). Given the fact that these would most naturally be understood as three successive days (Friday, Saturday, Sunday); and given that two Sabbath days (one weekly and one annual) are never explicitly distinguished as having fallen on two different days, the burden of proof is certainly on Ritenbaugh to prove that the Gospel writers intended us to see a five-day period encompassing the crucifixion and the discovery of Jesus’ empty tomb. As it stands, Ritenbaugh offers three dubious arguments for his conclusion.

First, Ritenbaugh relies on a highly debatable interpretation of the “70-weeks” prophecy in Daniel 9:24-27,2 and on a particular version of the Jewish calendar, to prove that (a) Jesus must have been crucified in AD 31 (as opposed to any other year between AD 30 and 33); and (b) in that particular year the Feast (Sabbath) of Unleavened Bread fell on a Thursday rather than a Saturday. Nevertheless, this argument is inconclusive for the following reasons: (a) Jews have not historically been able to agree on the details of their calendar;3 (b) No version of the Jewish calendar represents an infallible document like Scripture; (c) The Gospel writers give no hint that the timing of crucifixion-resurrection narrative can only be understood with reference to extra-Biblical sources.

Second, Ritenbaugh musters support for the view that the disciples visited the tomb after two different Sabbath days from the fact that the word for “Sabbath” in Matthew 28:1 (but not Mark 16:1) is plural, so that it allegedly should read, “Now after Sabbaths [plural]...Mary Magdalene and the other Mary came to look at the grave.” But Ritenbaugh, would seem to be unaware that “Sabbath,” like other words in the Greek Scriptures (e.g. birthday/genesiai), often has a plural form when a singular referent is in view. In fact, this phenomena (of a plural form with a singular referent) with respect to the word “Sabbath” has already occurred several times in the earlier chapters of the Gospel of Matthew (Matt. 12:1, 5, 10-12; cf. Mark 1:21; 2:23, 24; 3:2, 4; cf. Luke 4:16, 31; 6:2; 13:10; Acts 13:14; 16:13; Ex. 20:8; 35:3; Deut. 5:12; Jer. 17:2; etc.), without any hint that multiple Sabbath days are in view. (It may be that “Sabbath” commonly appears in its plural form because there was something inherently collective about it—it doubled as the word for “week”—as the culmination of seven days, just as “heaven” is often found in the plural, since it was commonly thought to possess different levels or regions.) In light of this pervasive use of the term, “Sabbath,” Matthew would have needed to use much more specific language to effectively communicate that two distinct Sabbaths had passed (e.g. “after two Sabbaths”), especially when only one Sabbath day is mentioned in the broad context. Additionally, given the fact that the parallel passages in Mark and Luke only envisages one Sabbath as having passed before the disciples visited the tomb on Sunday—“when the Sabbath [singular] had passed” (Mark 16:1; cf. Luke 23:56)—there would seem to be every reason to suppose that Matthew only has one Sabbath day in view as well.

Third, the most involved argument that Ritenbaugh advances for the view that there were two Sabbath days between Jesus’ death and resurrection hinges on the differing reports in Luke and Mark with respect to when the female disciples bought/prepared spices to apply to Jesus’ deceased body (a common part of the burial procedure). Luke indicates that the women began preparing the spices before the Sabbath (Luke 23:54-56). Mark, on the other hand, tells us that the women bought spices on the evening after the Sabbath. Allegedly, the only way that the women could have bought and prepared the burial spices both before a Sabbath day and after a Sabbath day is if there were two distinct Sabbaths in the same week with exactly one day in between. Of course, this is what Ritenbaugh proposes—a Sabbath on Thursday and a Sabbath on Saturday, with Friday in between. Again, Ritenbaugh’s argument is at best inconclusive, and at worst indicative of a blatant disregard for the details of the Gospel narratives. To begin, it is perfectly conceivable how the women might have prepared and purchased spices both before and after one Sabbath, without having to posit two Sabbath days in the same week. For, the women may have made an initial preparation of spices just after Jesus’ death on the Friday prior to the Saturday Sabbath (Luke 23:54-56), and then bought more spices after sundown on Saturday (the beginning of Sunday by Jewish reckoning) to complete their preparations for the Sunday visit (Mark 16:1). Indeed, perhaps the reason why the women merely prepared some spices on Friday without applying them to Jesus’ body immediately was because they needed to purchase more. There are several reasons why this sort of explanation is to be preferred over the one supplied by Ritenbaugh. For example, Luke places the women’s preparation of spices directly after Jesus’ body was removed from the cross (Luke 23:53-55). But, on Ritenbaugh’s scheme the women allegedly began buying and preparing spices two days after Jesus was crucified, with the result that Ritenbaugh must suppose that an unmentioned day and a half period elapsed between verses 53 and 54 of Luke’s narrative. Additionally, in both passages Luke and Mark speak of “the Sabbath” (using the definite article), as if there were only one Sabbath in view, as opposed to “a Sabbath,” as if one of multiple Sabbaths were in view (Luke 23:53; Mark 16:1). Finally, the fact that Ritenbaugh’s scheme cannot be derived from a straightforward reading of any single Gospel account (while the traditional scheme can be so derived from all four individually, and together) is indicative of its weakness.

In addition to the specious nature of Ritenbaugh’s arguments for a Saturday resurrection, it is noteworthy that the theory makes for several oddities. One wonders why the disciples, and especially the women interested in completing Jesus’ burial would wait until Sunday (the fifth day after the crucifixion on Ritenbaugh’s scheme) to visit Jesus’ tomb and apply spices to His body, when they could have come two days earlier, on Friday. In Matthew’s Gospel the angel at the tomb informs the disciples that Jesus “is going ahead of you into Galilee” (Matt. 28:7), as if He had risen from the dead shortly before they had arrived, and just set out on His journey. On the Saturday resurrection scheme, however, Jesus had already been risen for some 12 hours and was either making a very slow trip to Galilee, or had decided to remain around the tomb for half of a day before He set out. Taken alongside of the lack of any conclusive proof for a Saturday resurrection, curiosities like these point us to the fact that defenders of the Saturday resurrection theory are not driven to their conclusions by careful interpretation of the texts. Fundamentally, it is resistance to the (appropriately) felt ramifications that a Sunday resurrection has for Christian worship, coupled with a misunderstanding of the phrase “three days and three nights,” that governs their reading throughout.

Typological Significance of Time-Indicators

A final critique that may be leveled against Ritenbaugh’s seventh day resurrection theory is that the determination to attach a 72-hour meaning to “three days and three nights” leads one to overlook entirely it’s typological significance. The pertinent question with respect to Matthew 12:40 is why Jesus chose to speak of the general duration of His time in the tomb as “three days and three nights,” when a simple “three days” might have sufficed? The first answer is that Jesus wanted to draw a comparison between Himself and Jonah, about whom it is said that he remained in the belly of a sea monster for “three days and three nights” (Jonah 1:17). But this only raises the question a second time, why it was not simply said of Jonah that he was in the sea monster for “three days”? To these questions, the advocates of a Saturday resurrection respond that Jesus and the Book of Jonah were very concerned to convey that they were talking about a 72-hour period. (But, of course, we have already seen that this is a mistake, as the phrase normally need not be understood in this way.) A better, more Biblically informed answer is that Jesus and Jonah want us to see the respective events in light of the third day of creation. After all, Genesis 1:3-13 provides the first Biblical reference to three successive days, each of which was explicitly divided into “day” and “night” (Gen. 1:5), and therefore marked by the two transition points of “evening” and “morning” (Gen. 1:5, 8, 13). Notably, on the third of the three “day-night’s” of Genesis 1, God causes the unruly waters to recede so that dry land appears for the first time, rising above the watery abyss. Likewise, on the third day, Jonah (a man made of earth—Gen. 2:7) is raised up from the waters when the sea-monster “vomited Jonah onto the dry land” (Jonah 2:10). Likewise, on the third day after His crucifixion, Jesus is raised from the dead and taken from “from the heart of the earth” (Matt. 12:40).4 Throughout Scripture the depths of the sea and the grave are both described as regions of the dead, unfit for the living (Ps. 69:1-2; Ps. 130:1; Lam. 3:55; Jonah 2:2).5 Another divine act on the third day of Genesis 1 is the creation of all kinds of seed-bearing plants and fruit-bearing trees. Similarly, Jonah becomes the spearhead of a fruitful, even if reluctant, mission to Nineveh. Still more, Jesus is the “first fruits” of a resurrected humanity (1 Cor. 15:20, 23; Col. 1:16), who imparts His Spirit to the disciples to empower them for a worldwide mission (John 20:22; Acts 1:8). Hence, on the third “days” of creation, Jonah’s stay in the sea-monster, and Jesus’ stay in the tomb, a piece of earth rises from the depths to become a fruitful source of life to many. Ironically, because of their insistence on a technical 72-hour meaning for the phrase “three days and three nights,” advocates of the Saturday-resurrection theory: (a) fail to appreciate the powerful allusion to Genesis 1 in Jonah 1:17 and Matthew 12:40; and (b) effectively deprive the resurrection of any reference to the “third day” of creation. For, on the basis of a speculative construction of events they have Jesus rising from the dead on the “fifth day” after his death.

Another significant feature of the “third day” of the Genesis 1 creation narrative is that it follows: (a) a first day on which God creates light, and passes His first judgment on the creation, declaring it “good” (Gen. 1:3-5); and (b) a second day, on which God divides the waters on earth from the waters in heaven, but foregoes the passage of any judgment on the created sphere, so that of the second day alone does God neglect to evaluate “that it was good.” When God causes dry land and vegetable life to appear on the third creation day and pronounces it “good” (Gen. 1:9-13) it marks a resumption of the role of judge, and a turning point in His evaluation of the creation. In keeping with this notion of the “third” day (not to mention “third” months and years), scores of subsequent Scriptures have crucial turning points in judgment, either for blessing or for cursing, occurring on “third” days, hours, months, and years (cf. Gen. 22:4; 31:22; 34:25; 40:12-20; 42:17-18; Ex. 19:1, 11-16; Lev. 7:17-18; Lev. 19:6-7; Num. 19:12, 19; 31:19; Deut. 26:12; Josh. 9:16-17; Judg. 20:30; 1 Sam. 20:5, 12; 30:1; 1 Kings 12:12-15; 15:28, 33; 18:1; 22:1-2; 2 Kings 18:1; 19:29; 20:5-8; 2 Chron. 10:12-15; 15:8-15; 17:7; 31:7; Ez. 6:15; Est. 1:3; Is. 37:30; Jer. 52:30; Dan. 1:1; 8:1; 10:1-3; Hos. 6:2; Amos 1:1; Luke 13:32; John 2:1; Acts 2:15; 20:3; 23:23; 27:19; 2 Cor. 12:14, 13:1; etc.).6 In keeping with this third day judgment theme, Jesus’s trial/crucifixion, burial, and resurrection span three days. These events begin with an initial light of judgment at Jesus’ trial and crucifixion on the first of the three days. Next, Jesus remains “cut off” (Dan. 9:26) and divided from His people as His body lay in the tomb for the entirety of the second day, on which no new judgment occurs. Then, on the third day, Jesus is resurrected in accordance with a vindicating judgment from the Father. On Ritenbaugh’s scheme, this theme of a third day judgment, to which the Gospel writers repeatedly allude, is entirely lost.

The unanimous testimony of the Gospels that the tomb was found empty, and that Jesus had in fact risen from the dead on the “first day of the week” (Matt. 28:1; Mark 16:2; Luke 24:1; John 20:1, 19), and “after the Sabbath,” (Matt. 28:1; Mark 16:1; Luke 23:56) is undoubtedly intended to point us to another pair of significant numbers, namely, one and eight. Repeatedly throughout the Scriptures, the first/eighth day after a succession of seven days, represent newness—new beginnings, new life, new privileges, new light of revelation, etc. On the first day of creation, God creates light (Gen. 1:3-5), and on the eighth day after Peter’s confession of Jesus as the Messiah, Jesus appears in the brightness of His glory on the mount of transfiguration (Luke 9:28). On the first day, of the first month, of the six-hundred and first year the waters of the flood fully recede (Gen. 8:4, 13), enabling Noah to repopulate the earth as if he were a new Adam (Gen. 9:7). On the eighth day after their birth, that is, the first day after seven (Gen. 17:12; 21:4; Lev. 12:3; Luke 1:59; 2:21), Israelite males were to be circumcised, having a new identity confirmed as members of God’s priestly nation (Josh. 1:9; Col. 2:11; John 7:23). The Aaronic Priests could only assume their new responsibilities eight days after their consecration (Lev. 8:33-9:1). The altar of Ezekiel’s temple is only purified on the eighth day after seven days of cleansing (Ezek. 43:27). Those who had infectious skin diseases and sores, and those who were defiled by contact with dead bodies pass through seven days of relative isolation before being restored to vital communion with other believers on the eighth day (Lev. 14:9-11, 23; 15:14, 29; Num. 6:10). The Feast of First-Fruits occurs on the first day of the week, often on the day right after the Feast of Unleavened Bread (Lev. 23:7, 10-15). The Feast of Pentecost follows fifty days after First Fruits, that is, on the first/eighth day after seven weeks (Lev. 23:15); and it requires the presentation of “a new grain offering to the Lord” (Lev. 23:16). The Feast of Booths begins on the fifteenth day of the seventh month, that is, on the first/eighth day after two weeks of days (Lev. 23:34, 39; Num. 29:12). After the Israelites dwell in booths for seven days to commemorate their wondering in the wilderness, the eighth day (Lev. 23:36; Ezra 8:18) is a day of celebration of the new life granted to the Israel when they entered the Promised Land. Hence, it is no coincidence that the Gospels expressly teach that Jesus, the “firstborn from the dead” (Col. 1:18; Rev. 1:5) is “first fruits” of a new and resurrected creation (1 Cor. 15:20, 23), risen from the dead on the first/eight day of the week, Sunday. Again, the Saturday resurrection theory strips the resurrection of its connection to the rich first/eighth day theme that pervades Scripture.

On the traditional Sunday-resurrection scheme, even the time of day on which Jesus rose from the dead—“early in the morning,” at “dawn” (Matt. 28:1; Mark 16:2; Luke24:1; John 20:1)—carries with it significant connotations. For, throughout the Old Testament, the dawn of morning is often used as an image for an expected future period of blessing and deliverance from oppression and death. “His anger is but for a moment, His favor is for a lifetime; weeping may last for the night, but a shout of joy comes in the morning” (Ps. 30:5); “As sheep they [the wicked] are appointed for Sheol; death shall be their shepherd; and the upright shall rule over them in the morning…God will redeem my soul from the power of Sheol” (Ps. 49:14-15; see also Ps. 110:3; 130:6); “Then your light will break out like the dawn, and your recovery will speedily spring forth” (Is. 58:8; see also Mal. 4:2; Hos. 6:3). Not surprisingly, then, Jesus who rose from the dead early in the morning on Sunday, identifies himself as the “bright morning star” (Rev. 22:16). If God’s compassion is expressed “[a-]new every morning” (Lam. 3:23), along with His justice (Zeph. 3:5; Job. 7:18) and His empowering strength (Isa. 33:2), then the same divine attributes were preeminently expressed on the morning of Jesus’ resurrection and vindication (Rom. 1:4; 1 Tim. 3:16). Yet, the Saturday resurrection view deprives Jesus’ resurrection of any association with the morning, since it has Jesus rising at 6:00 PM on Saturday.

Hence, the Saturday resurrection theory effectively disassociates the events of Jesus’ death, burial, and resurrection from the significant timeframes and time references that are explicitly mentioned with respect to Christ’s death and resurrection (“three day and three nights,” “the third day,” “the first day,” and “morning”), all in the interest of forcing the resurrection account comport with the unbiblical assumption that the phrase “for three days and three nights” necessarily means “spanning exactly a 72-hour timespan.”

Conclusion

In this article we have defended the view that only a Sunday resurrection: (a) comports with the details of the crucifixion-resurrection narratives in the Gospels; (b) retains the profound typological associations supplied by the major timeframes and references to the Resurrection; (c) embraces a Biblical understanding of the meaning of “three days and three nights” as denoting a general three-day timeframe; and (d) is naturally derivable from all four Gospels independently and together. Hence, insofar as the timing of Christ’s resurrection is instructive for when His people ought to enter into His presence in corporate worship, the practice of Sunday worship rests on the firmest Biblical footing.

_______________________________

- Although it does not bear directly on the question of whether Jesus rose on a Sunday (a matter on which, we will see, the Gospel writers are clearly united), the construction that we have offered above presupposes that the Last Supper took place on what we would call Thursday evening. (However, reckoning days from evening to evening, the Jews would have viewed the Last Supper as having occurred on the first part of Friday, that is the night before the lambs were slaughtered for the official Passover meal.) In this case, the Last Supper would have been significantly connected to the official “Passover” meal, since it occurred on the same day. There can be no doubt that it was intended by Jesus to function as replacement of the Passover meal, since He expected to be crucified the following evening (Matt. 26:20-25). For a thorough defense of this view see R.T. France, The Gospel of Mark (Grand Rapids: Eerdmands, 2002), 559-563.

- The many issues involved in interpreting Daniel’s 70 weeks prophecy are too numerous to be properly handled here. Suffice it to say that there are numerous interpretations of Daniel 9, several of which allow the 69 weeks to terminate at the beginning of Christ’s ministry, and the atoning death of Christ to occur in the middle of the 70th week, which do not involve placing the death of Christ in AD 31. See James B. Jordan, The Handwriting on the Wall (Powder Springs, GA: American Vision, 2007), 469-475. Kenneth Gentry, He Shall Have Dominion (Draper, VA: Apologetics Group Media, 2009), 309-322. E.J. Young, A Commentary on Daniel (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1949), 191-221.

- As R.T. France notes, some have attempted to resolve the apparent conflict with respect to the timing of the Passover between the Synoptic Gospels and the Gospel of John, by suggesting that they reflect two different interpretations of the Jewish calendar. France, Mark, 559.

- It may very well be that Matthew’s reference to the “heart of the earth/land” is a double entendre, that refers both to Jesus position within a mound of earth, and to his position in the midst of Israel which is often referred to as the “land.” See James B. Jordan, “In the Fish; or, The Church As Tomb,” at http://www.sabbath.org/index.cfm/fuseaction/Library.sr/CT/CGGBOOKLETS/k/419/subj/sabbath/After-Three-Days.htm.

- It should be noted that the “sign of Jonah” which Jesus was in some respects to reproduce has many more connotations than the mere descending beneath the earth and rising again after three days. Another association which would have been at the forefront is that Jonah was granted new life only so that he could go on to bless a people whom he despised (Assyrians), in place of the rebellious house of Israel from whom he was taken. Likewise, shortly after Jesus’ resurrection, the blessings of the kingdom of God is extended to the Gentiles, in place of yet another rebellious house of Israel. Hence, the “sign of Jonah” is a sign of condemnation to Israel, and blessing to her enemies. On this topic see, James T. Dennison, “The Sign of Jonah,” Kerux 8/3 (1995), 31-35; available at http://www.kerux.com/documents/KeruxV8N3A3.asp.

- I am indebted to James B. Jordan for this observation.

_______________________________

Brant Bosserman lives in the greater Seattle area with his wife Heather and four children — two 11 year old girls (Nicea and Chalcedon), and his 8 and 5 year old boys (Augustine and Calvin). He is the planter/minister of Trinitas Presbyterian Church, in Mill Creek, WA (PCA) which was launched in May 2013, and particularized in October 2015. He has his PhD in philosophy of religion from the Welsh, Bangor University. His M.A.T is from Fuller, and his B.A. in Religion & Philosophy/Biblical Lit is from the Pentecostal University, Northwest U., where he has taught philosophy courses in an adjunct capacity for over 10 years. He is a Van Til scholar, and published “The Trinity and Vindication of Christian Paradox” available here.