100 Years of Reformed Presbyterian Missions in Syria (Part 1 of 2)

This is part 1 of a 2-part series on the RPCNA mission to Syria, from 1856 to 1958. Part 1 will provide an historical overview of the mission. Part 2 will analyze and evaluate the missiological methods employed.

Note: The picture above is from page 194 of the Herald of Christian Missions (1890). The following page states, "With the exception of the first person on the left of this picture, we have here represented some of the workers in the newly-organized congregations in our mission in Syria."

In 1856, the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America sent their first missionaries to a foreign field.[1] The foreign field was Syria, and the mission work that began was to continue for just over a century. In all, least seventy missionaries served there.[2] At least seventeen of those missionaries died there, and at least ten of their covenant children were buried there.[3] The last words which have been preserved to us testify to the Covenanter faith which sustained the missionaries throughout their labors.[4] An analysis of their methods will provide valuable insights for future R.P. missions in equally difficult fields.

Three books written by Covenanter missionaries provide a window into the work. The first is J. M. Balph’s Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria, summarizing the work until 1913. The second is A. J. McFarland’s Eight Decades in Syria, published in 1937. The last is Marjorie Sanderson’s A Syrian Mosaic, written after 18 years after she and her husband left Syria at the close of the mission in 1958. In addition to these books, there are also copious other first-hand missions update letters in the missionary journals as well as the deliberations recorded in the minutes of synod in America.

Those who have read these books will understand that a window into the work is a window into another world. Every passing detail has its entire backstory, and what is mentioned in one book is often illumined more fully in another, until the reader gets a tantalizing sense of the fullness of 100 years in Syria. The apostle John’s observation of Jesus’ life rings true: “there are also many other things … which if they were written one by one, I suppose that even the world itself could not contain the books that would be written” (John 21:25, NKJV).

Religious Landscape

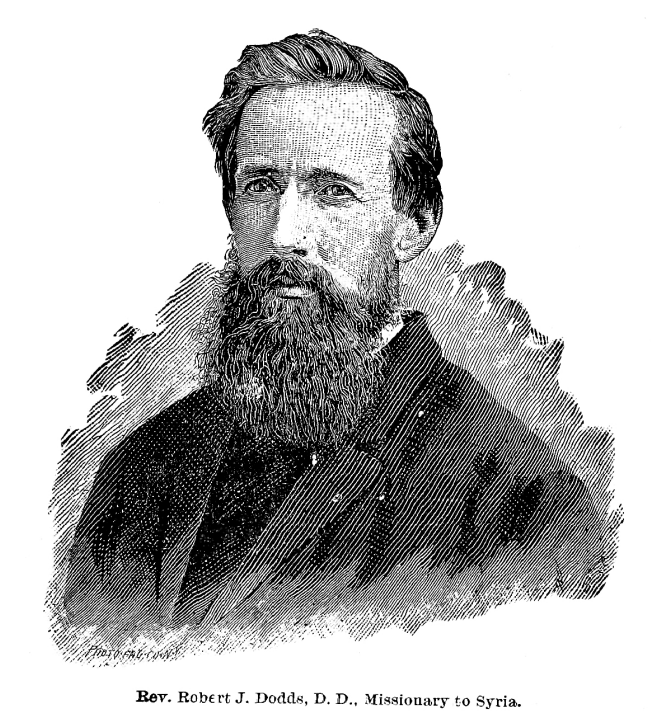

On October 16th, 1856, pioneer missionaries Robert and Letitia Dodds and James and Martha Beattie set sail for Syria from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, with the help of a returning Dutch Reformed missionary as a travelling companion.[5] Forty-nine days later, they arrived in Beirut, Lebanon and travelled by caravan to Damascus.[6]

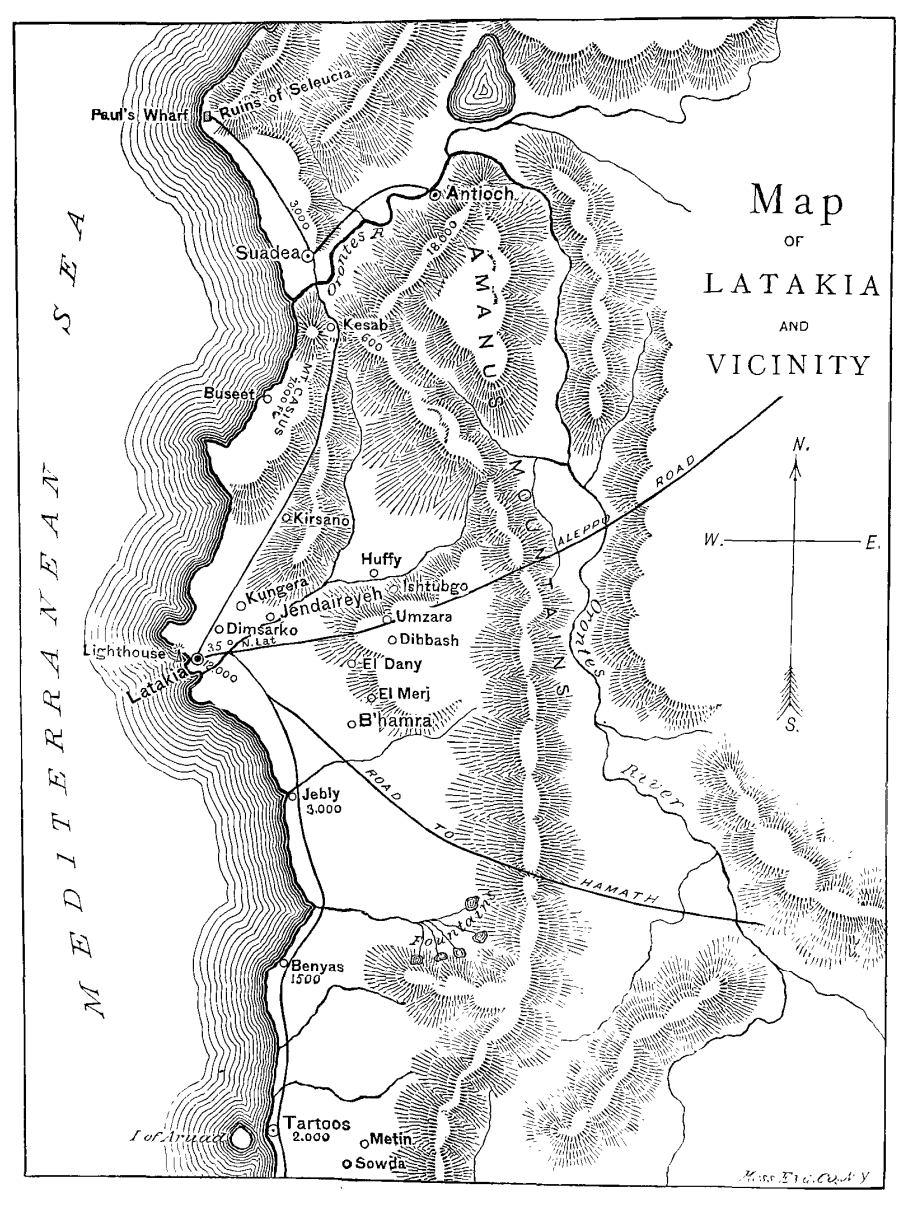

The religious landscape was mixed. Perhaps surprisingly, the Greek Orthodox church was the first to oppose the work. Greek Orthodox priests entered Dodds’ first residence in Zahle, Lebanon and tossed “the greater part” of his library onto the street before he agreed to leave the city.[7] The search for a new base of operations commenced, and the port city of Latakia, Syria was chosen.[8]

In Latakia the missionaries were confronted with another religion: the Alawites, so named for the sun-God Ali whom they worshipped,[9] who were also known as the Nusairiyeh from their abode in the Nusairiyeh mountains surrounding Latakia.[10] There were over seventy-five thousand Alawites in Latakia,[11] and another four thousand five hundred in Adana near Mersine, “to whom the new work was chiefly aimed.”[12] Marjorie Sanderson encapsulates the continued focus on the Alawite people in a story of her final goodbye as she was leaving Syria: “Our predecessors had come to preach the Good News to the Alaouites. The last friend to bid us goodbye was a young man graduate of 1958 who was working on the ship as a tally man. He was an Alaouite who had accepted Christ as his Saviour while attending our high school.”[13]

The Alawites claimed to be descendants of the Canaanites and practiced a syncretistic religion of animism and Islam.[14] According to McFarland,

It was known therefore that one of the “distinctive principles” of this religion is that one should play the hypocrite when in the midst of a stronger people of another religion. So we find them out of “respect” to the Moslems, who have so long been their masters, teaching the Koran to their children and using Moslem names as Ali from which comes their name, Alaweets, and Mohammed, the prophet honored by the Moslems. But the initiated among them know that Ali, as they use it, refers not to the Moslem saint of that name but to The Sun, and Mohammed also means to them The Moon.[15]

The Alawites also believed that the souls of their men pre-existed with God in heaven as stars, so that Sanderson correctly observed that “the people worshipped the sun, moon and stars.”[16] The Alaweets believed that the sin of pride led to their banishment to the earth, but by keeping their religion they would be received again by a star after death. From the sin of man, God created demons, and from the sins of demons he created women, whose souls were not eternal and who were therefore treated very poorly.[17]

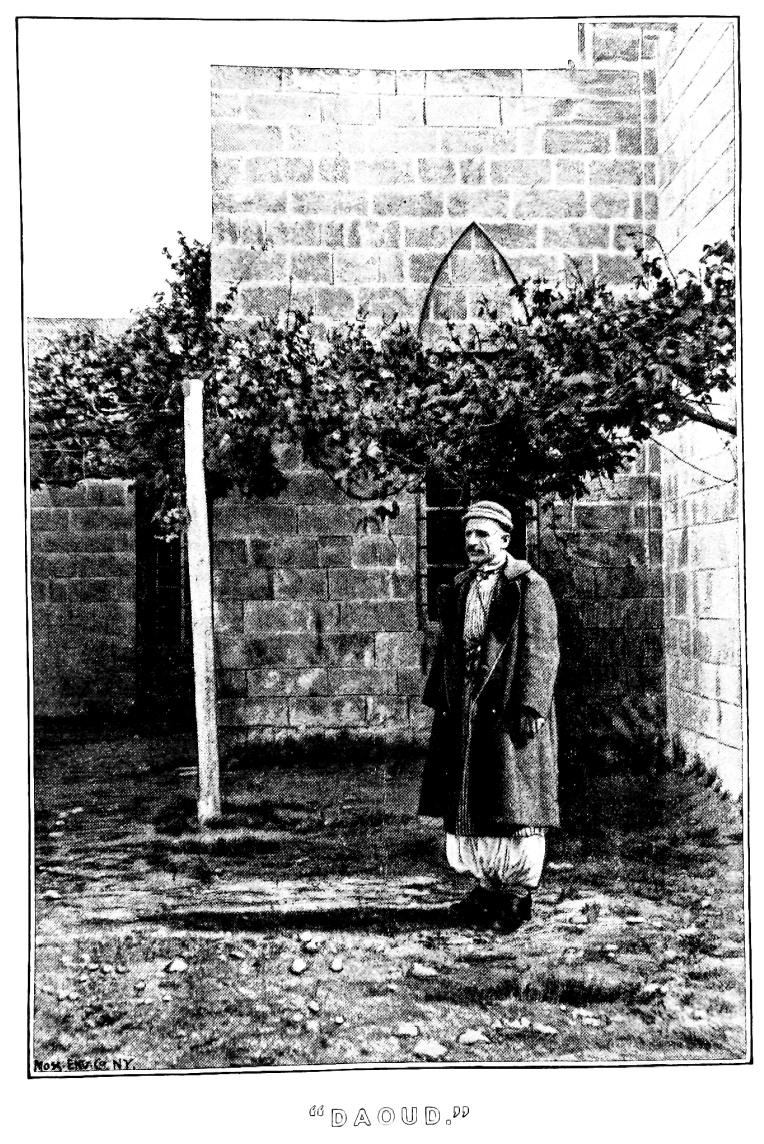

The secrets of the Alawite religion were only revealed to young men after an initiation ceremony in which they swore allegiance and secrecy on pain of death and mutilation of the body.[18] Such an oath made conversion difficult, and two of the first R.P. converts were Hamoud and Daoud who were not yet initiated.[19] This did not mean, however, that they were not persecuted for changing their religion. Both Hamoud and Daoud were tortured for their faith,[20] and Daoud was eventually delivered over to the Turks and forcefully conscripted to fight against the Russians on the frontier.[21]

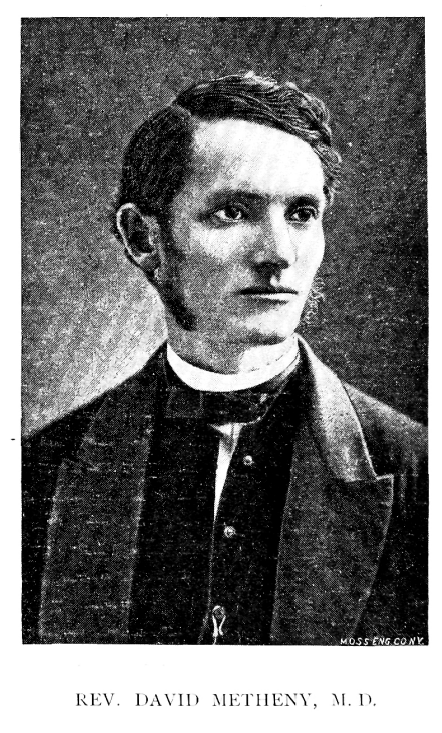

The majority religion, of course, was Islam. Muslims were never the main focus of the Syrian mission. They are generally only referenced in connection to mob violence or government persecution. Nevertheless, there were many Muslim converts. Dr. Methany in Mersine remarked “what a strange congregation I have when all are gathered together. Jews, Moslems, pagans, Greek Orthodox, Armenian, Catholic and Maronite.”[22]

Other Mission Fields

The Covenanter missionaries were blessed to be the recipients of other mission stations in the Levant. In 1860, the Anglican missionary Samuel Lyde died as a result of wounds suffered at the hands of the Alawites. In his will he deeded his mission station in Bahamra to the Covenanters.[23] In 1867 Free Church of Scotland mission stations in Aleppo and Idlib were reopened following an Alawite rebellion against the government and given to the Covenanters.[24] In 1874, an English medical doctor Holt Yates died and his widow transferred their compound in Suadea (which had been badly damaged in an earthquake two years prior) to the R.P. mission.[25]

In 1882, the Covenanters themselves opened up another mission field in Asia Minor. Preliminary work was done in the cities of Adana and Tarsus, but eventually the port city of Mersine, Turkey became the site of another mission compound.[26]The Mersine field was conducted in Turkish rather than Arabic and eventually focused more on the Armenians than the Alawites. The Mersine station was forced to close in 1922 following the decimation of the Armenian population by genocide during World War I.[27] Finally, in 1889 a mission station in Suadia was transferred from the Free Church of Scotland to the RPCNA,[28]and continued there until 1920 when it was transferred to the Reformed Presbyterian Church of Ireland and the Reformed Presbyterian Church of Scotland.[29]

Wars and Rumors of Wars

The mission work in Syria was bookended and punctuated by wars. It began in October 1856, only eight months after the end of the Crimean war, and it ended in August 1958 with the formation of the short-lived United Arab Republic following the Egypt’s success in the Suez Crisis of 1956.[30] In between there was continued fighting with Russia, a coup, and two World Wars, both of which saw Syria allied with America’s enemies.

The mere fact of war, however, did not necessarily mean an anti-Western sentiment. In fact, the Crimean War proved to be beneficial to missions. A. J. McFarland served in Syria from about 1906[31] to 1938[32] and wrote a book at the end of his tenure documenting the first Eight Decades in Syria. In it, he writes of the “propitious” beginnings of the mission:

The time, the place and the persons were well chosen. The Crimean War had just ended. Turkey had been wrested from the deadly embrace of the Russian Bear by the British and French and saved from a "benevolent assimilation" by Russia, which would have made Turkey as inaccessible to Protestant missionaries as Russia has always been. British and, incidentally, American prestige in Turkey were thus greatly increased, and our missionaries found access to the country less difficult than it might otherwise have been.[33]

The British and French had intervened in the Crimean War to preserve the Ottoman Empire, whose destruction risked upsetting the balance of power in Europe. However, the Ottoman Empire itself was not stable. Wars with Russia continued in the background, sometimes erupting into the fore.[34] In 1908, the “Young Turks” overthrew the Sultan and established a constitutional government.[35] Their modernizing reforms at first seemed beneficial to missions.[36] Suddenly, however, Turkish nationalism turned against the Armenian Christians, resulting in a massive genocide in the city of Adana.[37] Contemporary reports which have proven justified estimated the death toll to be around 25,000.[38]McFarland describes these 1909 massacres as “the dying spasms of the reactionary forces opposed to the operation of the new constitutional government.”[39]Unfortunately, this was not the first massacre of Armenian Christians, and it would not be the last.

By this time the Covenanters had a mission field in Mersine, Turkey as well as the original field in Latakia, Syria. Armenian refugees from Adana flooded into the missionary compound in Mersine. The Turks then continued southward toward Latakia,[40] where Covenanter medical missionary Dr. J. M. Balph helped treat the over eight thousand refugees that fled into the mission compound.[41] The purchase of additional wheat with funds sent from America to feed the Armenian refugees further incensed the Muslim Turks. R.P. missionary Samuel Edgar relates that “the Moslems of Latakia said, ‘Isn't it a shame to be feeding good wheat to those Armenian dogs? Let us clean them up.’ They sent out a man with a drum to call for a massacre of all refugees in the American compound.”[42] It was only the arrival of a British warship that ensured the safety of the missions compound, further highlighting the complex relationship between Western military hegemony and the progress of missions.[43]

In 1914 the outbreak of the first World War posed new problems for the R.P. missionaries. Most of the missionaries fled or were forcibly deported, especially those with British passports (since America had not yet taken sides in the war). Finally, only the Stewarts were left in Latakia, and soon after Mr. Stewart was forcibly detained and marched away to Konya, Turkey, where he was kept under guard until the end of the war. Thankfully, he was allowed some liberty to continue his missionary labors, so long as reported daily to the guard.[44] His wife remained to oversee the mission school.

With the defeat of the Central Powers, the League of Nations gave the French oversight of Syria. The effect on missions was mixed. Roads improved, making travel easier.[45] However, the government established a new hospital in Latakia which undercut the mission hospital by providing free treatment to the poor.[46] McFarland summed it up this way: “While life is much pleasanter under the flag of the French, it was really more thrilling under the Turk.”[47]

1939 confronted the Covenanter missionaries with a similar predicament with the start of the second World War. As the Axis armies advanced, the Covenanter missionaries again decided to leave some missionaries on the field in order to look after the mission schools in Latakia. By God’s providence, Latakia was spared bombing and the war provided an opportunity for evangelism and spurred interest in learning English.[48]

The Second World War, the deadliest war in history, with over sixty million casualties, could not bring the mission in Syria to an end. Yet a few years later, another conflict so small it is only referred to as the Suez Crisis, with fewer than six thousand casualties, did. During the Suez Crisis of 1956, Egyptian president Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal and then successfully defended himself against Israeli, British, and French forces which sought to remove him from power. Nasser’s popularity led to the creation of a short-lived United Arab Republic between Egypt and Syria, with Nasser as president. Anti-missionary pressure had already been building since 1955, and one by one the missionaries were expelled.[49]When American marines landed in Lebanon to protect them from U.A.R. expansion, the remaining missionaries were put on the “Unwanted List” and forced to leave on August 7th, 1958. As R.P. historian Bill Edgar writes, “The door which war opened, revolution and war closed.”[50]

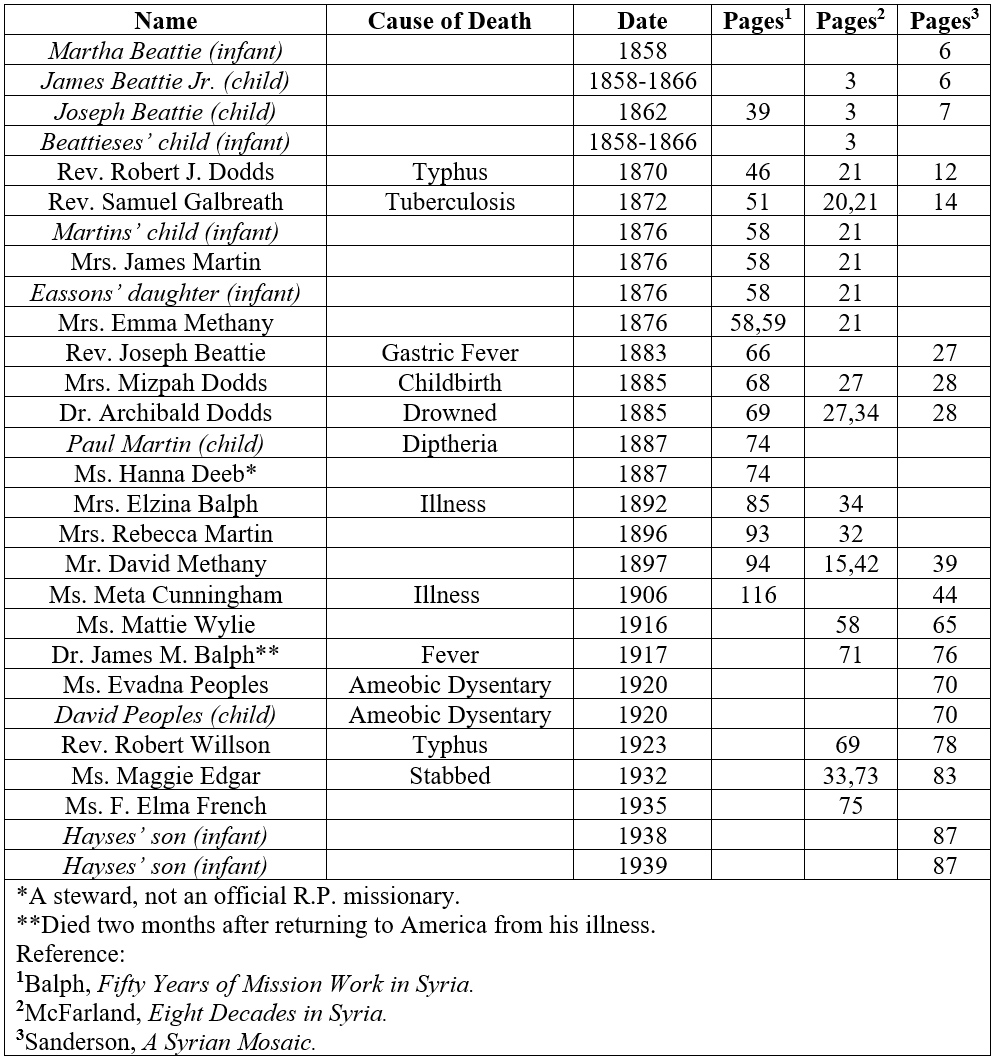

Appendix: Deaths

[1] Marjorie Allen Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: RPCNA, 1976), 1.

[2] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, in a chart entitled “Missionaries Serving the Covenanter Church in Syria” at the beginning of the book.

[3]See Appendix: Deaths.

[4] When the pioneer missionary James Beattie’s second child died, his fellow missionary Robert Dodds wrote: “The parents do not sorrow alone for our number is so small, and we are so much like one family, that the loss of the least in our little circle is a sore breach upon us all... We have bought a burying place in the land of our sojourning. May it be to us as Abraham’s was to him, an earnest of the future possession of the whole land.” Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 6. Dodds himself, knowing he would die soon at age 46, whispered, “It is the father’s time.” Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 12. Dr. Methany’s last words were, “I long to be with Jesus.” Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 39. Towards the end of the mission, after the death of Evalyn Hays’ second infant son after 40 days, wrote, “What joy we have when we know we are to receive something, but are we willing to give it back? Our hearts have been searched, and He knows when we pray ‘Thy will be done,’ whether we mean it or not. Let us pray this petition with sincerity.” Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 87. These few quotes, however, are just a sampling.

[5] J. M. Balph, Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Press of Murdoch, Kerr & Co. 1913), 13.

[6] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 1.

[7] A. J. McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria (Topeka, Kansas: RPCNA, 1937), 4-5. See also Balph, Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria, 17. Interestingly, a mission work by other protestants seems to have continued there, and among the converts were those who had originally driven Dodds out by stoning. Balph, Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria, 57.

[8] McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 5. See also Balph, Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria, 19.

[9] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 4.

[10] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 3. See also Balph, Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria, 31.

[11] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 3.

[12] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 26. See also McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 10. Eventually, it appears that the work in Mersine eventually came to focus more on the Armenians. William J. Edgar, History of the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America 1871-1920: Living By Its Covenant of 1871 (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Crown and Covenant, 2019), 135.

[13] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 107.

[14] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 3.

[15] McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 9.

[16] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 4.

[17] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 4. See also McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 9-10, and Balph, Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria, 33-34.

[18] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 4. See also Balph, Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria, 34.

[19] If Daoud is the same young man referred to as Yusuf Jadeed in McFarland’s account, then both Hamoud and Daoud were pupils of an Anglican missionary Samuel Lyde, who had begun a work among the Alawites but “had reached the end of his strength” and “was quite ready to hand over his work to our pioneers on their arrival.” McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 1. Hamoud was converted after his beloved teacher (Mr. Lyde) was lured to an Alawite village and beaten almost to the point of death, yet forbid his friends from seeking vengeance before he died a few months later from his wounds. McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 13.

[20] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 5.

[21] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 18. See also McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 28, 43.

[22] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 27.

[23] Balph, Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria, 36. See also McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 18.

[24] Balph, Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria, 44. See also Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 10 and McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 19.

[25] Balph, Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria, 54. See also Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 26 and McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 18.

[26] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 26. See also McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 29, where it is referred to as the “Tarsus mission” and Balph, Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria, 64-65.

[27] Edgar, Founding Churches in Ottoman Empire Territory, n.p.

[28] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 34, 36. See also McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 19. Not to be confused with Suadea, a town north of Latakia, where a mission complex was also given to the Covenanters in 1873. Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 26.

[29] Nathaniel Pockras, RPCNA Digest and Index: Actions of the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America since 1798 (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Crown and Covenant, 2021), 134. Reference is made to “the Scotch-Irish mission north of us” in McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 29.

[30] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 107.

[31] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 45.

[32] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 87.

[33]McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 1.

[34] Balph, Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria, 59.

[35] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 45.

[36] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 46.

[37] Balph, Fifty Years of Mission Work in Syria, 128-131. See also McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 52-55, and Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 46-51.

[38] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 47.

[39] McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 54-55.

[40] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 49.

[41] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 50.

[42] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 49-50.

[43] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 49.

[44] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 64-68. See also McFarland, Eight Decades in Syria, 61-62.

[45] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 82.

[46] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 83.

[47] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 82.

[48] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 88.

[49] Sanderson, A Syrian Mosaic, 100.

[50] Bill Edgar, Founding Churches in Ottoman Empire Territory: RP Foreign Missions, 1856-1974, written June 13, 1998, accessed April 2021, https://broomallrpc.org/articles/founding-churches-in-ottoman-empire-territory.