Under One Crown: The Church, the State, and Christ’s Mediatorial Rule

If someone becomes an officer in the RP Church, their 5th vow of ordination includes the following: "Do you believe it to be the teaching of Scripture—that church and state are distinct and separate institutions; that both are under the mediatorial rule of the Lord Jesus Christ..." What in the world does that mean? How can Jesus be both the mediatorial king over the church and the state, yet they are considered "distinct and separate institutions"?

To answer that, we’ll take a quick run through history, examining seven different views of church and state in the Western world. Before we dive in, let’s first define the key concept of Christ’s mediatorial rule.

Christ’s Mediatorial Rule Over Church and State

The phrase “mediatorial rule” refers to Christ’s sovereign kingship as the appointed Mediator between God and man. Jesus, as the God-Man, reigns over all things by divine right. His rule is often categorized in two ways:

First, Christ exercises His kingship in the spiritual realm. He does this by ruling over the Church, which He has redeemed through His blood. This is a direct, saving rule. Jesus governs His people by His Word and Spirit, leading them to eternal life.

Secondly, as Mediator, Christ also governs the nations and civil magistrates. Though distinct from His redemptive rule, this providential reign ensures that all earthly authorities are subject to Him. His rule over them is not dependent on whether they acknowledge it or not. Christ rules through the civil magistrate to maintain order, execute justice, and restrain evil.

This dual aspect of Christ’s kingship is explicitly articulated in the Westminster Confession of Faith (WCF), Chapter 23, “Of the Civil Magistrate.” We confess Christ as the ultimate ruler even in civil matters:

"God, the supreme Lord and King of all the world, hath ordained civil magistrates, to be, under Him, over the people, for His own glory and the public good…"

Yet, the Confession also stresses the distinction between church and state:

"Civil magistrates may not assume to themselves the administration of the Word and sacraments, or the power of the keys of the kingdom of heaven…"

Both institutions operate under Christ’s authority but with distinct roles. The church wields spiritual authority through the Word and sacraments. The state wields temporal authority through the sword. Understanding how these roles have been perceived and implemented throughout history helps illuminate the biblical teaching on their proper relationship.

Now, let’s explore seven historical models of church-state relations to see how this doctrine has been understood (or misunderstood) over time.

***Disclaimers

- I am writing briefly and with broad brush strokes; don't expect too much nuance. Also, these are not hermetically sealed and rigid models. There are times and examples of overlap. You can disagree with my categories as well.

You can click on any one of these seven to jump to that section:

- State Enforced Religion

- Religion Dominant Governance

- Two Kingdoms Collaboration

- Radical Church State Separation

- Neutral Governance

- Moral Influence Model

- Secular Suppression

State Enforced Religion

When Government Dictates Worship

We'll pick up the story of the church and state's relationship in the Roman Empire. State-Enforced Religion was a cornerstone of the Roman Empire. Political and religious authority were deeply intertwined. In this system, the government dictated worship practices. There was a blending of state control with religious observance to maintain societal order and imperial unity.

How did the Roman State Enforce Religion?

In Rome, the government and religion were two sides of the same coin. Emperors like Julius Caesar and Augustus were seen as semi-divine figures. Later, emperors were outright deified. Citizens were expected to honor them as gods. This wasn’t just about personal piety. Worship was a public declaration of loyalty to the empire. If you refused to worship the emperor, you weren’t just seen as irreligious; you were a traitor.

Rome had an official pantheon of gods. Sure, they accumulated and imported them, but their worship was not optional. No, worship was a civic duty. Temples were built and paid for by the state, and festivals were sponsored to honor these gods. The belief was simple: if you kept the gods happy, they’d keep Rome strong. But if you upset them? Plagues, pestilence, wars, or worse. The government took religion very seriously. For the good of the empire, they had to make sure everyone participated in these public rites.

Religion was essential in keeping the empire together. If you disrupted the religious system, you weren’t just being a troublemaker—you were putting the whole empire at risk. This is why Roman officials were so harsh on Christians. They weren’t just worried about what Christians believed; they were worried about what those beliefs could do to the state.

The state supported, enforced, were a part of, propagated, and in many ways were in themselves part of the religion. There was functionally one kingdom.

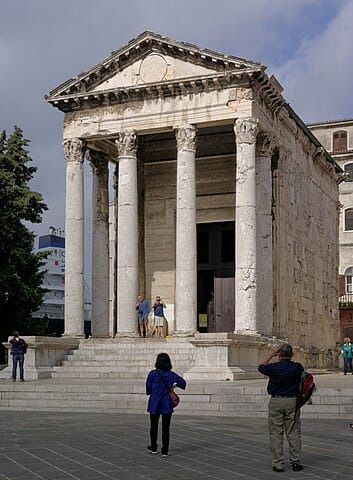

However, in 330 AD, when Constantine moved the capital from Rome to Constantinople (very humble naming if I may say so), Rome, the city, seemed almost immediately to fade. Italy was under attack as early as 390, and the peninsula with the glory of her ancient city would begin to fade. The vacuum of power gave rise to a new system of church and state relationship.

Religion Dominant Governance

The Church Ascends

When the Roman Empire fell, the structure of state-enforced religion collapsed with it. The once mighty emperors, who had blended religious and political authority, gave way to the church stepping into roles previously held by the state. As political chaos spread, the church became a stabilizing force, often wielding significant political power to preserve order.

Religion began to dominate the government. This was essentially flipping the whole system on its head. It was no longer the king controlling the priests, but the priests over the kings.

The church didn't just influence the state; it often dominated it. Religious leaders began to exercise significant political power, shaping the course of history. We'll explore this shift by looking at three pivotal moments: the rise of Pope Leo I, the influence of Gregory the Great, and the crowning of Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor.

Pope Leo I: Steps into the Power Vacuum

Let’s start with Pope Leo I, also known as Leo the Great. By the mid-5th century, the Roman Empire was crumbling. Emperors were either too weak or too far away to protect the city of Rome itself. That’s when Leo stepped in.

In 452 AD, Attila the Hun—yes, that Attila who was murdering and conquering the world—was swiftly riding toward Rome. Where was the emperor? Nowhere to be found. So who meets Attila to seek peace? The Bishop of Rome! Leo convinced Attila to turn around and spare Rome. No one knows exactly what Leo said, but it worked. A few years later, in 455 AD, the Vandals showed up and were ready to sack the city. Again, it’s Leo who steps in. He couldn’t stop the looting, but he negotiated to prevent mass slaughter and burning.

Think about that: the Bishop of Rome wasn’t just praying for peace; he was actively negotiating with barbarian warlords. He wasn’t just leading the church. Leo was leading the city. This marked the beginning of the church stepping into political roles previously held by the state.

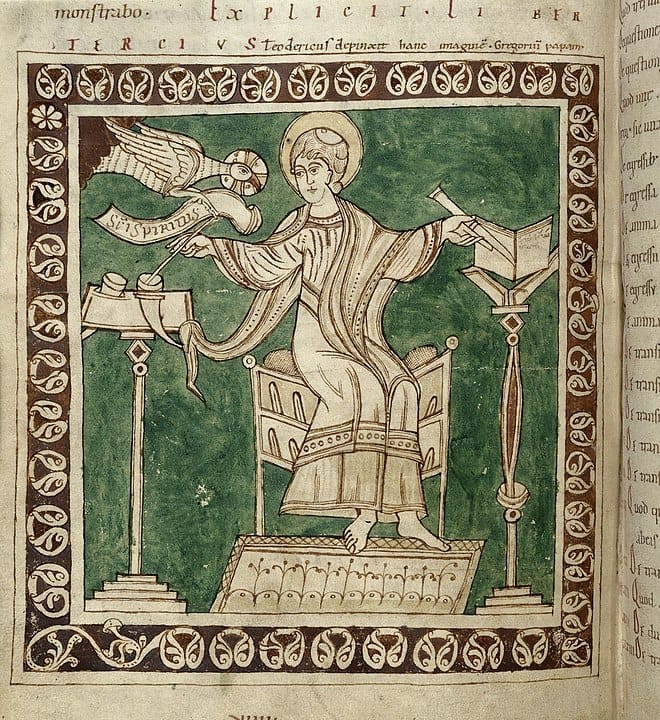

Gregory the Great: Rome’s New Administrator

Fast forward about 150 years, and you’ve got Gregory I, or Gregory the Great. By the time Gregory became pope in 590 AD, Rome was in even worse shape. The city was overrun with poverty, famine, and threats from invaders like the Lombards. Where was the Roman government? Practically nonexistent.

Gregory picked up the slack. He used the church’s wealth to feed the poor, maintain public services, and even broker peace treaties. He wasn’t just a spiritual leader. No, Gregory was acting like a mayor or even a governor.

Gregory organized food distribution for the city’s starving population. He ensured the city’s infrastructure, like the aqueducts and defenses, kept running. And Gregory dealt directly with Lombard leaders, securing peace when the Roman military couldn’t.

Under Gregory, the church became more than a place of worship. Religion became the backbone of society. Gregory saw this as part of the job. He was to care for both the spiritual and physical needs of the people. He called himself the “Servant of the Servants of God." Make no mistake, though: Gregory was running the show in Rome. The Bishop of Rome was, for all intents and purposes, ruling Rome.

The Crowning of Charlemagne: The Church Makes a King

Now let’s jump to 800 AD. By this time, the church’s influence had grown even stronger. On Christmas Day, in the grandest church in Rome, Pope Leo III did something revolutionary. Leo crowned Charlemagne as the first Holy Roman Emperor.

This wasn’t just a political ceremony. By placing the crown on Charlemagne’s head, Pope Leo was making a statement. The church is the ultimate authority, even over kings and emperors. The Roman Empire was not dead. The Empire was protected by the emperor, but the true authority was in him who placed the crown upon the emperor's head. Charlemagne might have been the most powerful man in Europe. He may have been able to fight back the Muslim advance into Europe. But his power was now seen as coming from the church.

This was a big deal. In the Roman Empire, emperors had controlled religion. Now, the church was crowning emperors. The power dynamic had flipped, and the church was on top.

The church wasn’t just influencing government. No, the church was actively deciding who held political power. The pope himself was seen as the ultimate moral authority, giving him leverage over kings. This period laid the groundwork for the medieval system, where the church and state were deeply intertwined.

With no strong central government and a need for survival, the church stepped in to fill the void. But this also set the stage for centuries of tension between popes and kings, as both vied for ultimate authority. The church has become a political powerhouse, shaping the course of Western history. Eventually, the Papal States would accumulate massive wealth, prestige, power, and a military of their own.

All of this would start to change with "the ramblings of a drunken German monk."

Two Kingdoms Collaboration

By the medieval period, the church wasn’t just influencing governments. No, the church was crowning kings and shaping empires. But the Reformation brought a major shift. Reformers like Luther and Calvin argued that church and state should remain distinct, even as both served under Christ’s authority. This new model called for a careful collaboration, where each focused on its God-given role.

Things moved from governments controlling religion and religion controlling governments to something new: Two Kingdoms in Collaboration. This model was rooted in the idea that God governs the world through two distinct but complementary realms—the spiritual and the temporal. These realms overlap, but each has its own unique responsibilities and authority. The idea was not brand new but had been advocated by Augustine in his work The City of God. In it, Augustine wrote in 426 AD:

“The earthly city, which does not live by faith, seeks an earthly peace, and it limits the harmonious agreement of citizens to the attainment of purely earthly goods. The heavenly city, or rather the part of it which sojourns on earth and lives by faith, makes use of this peace only because it must, until this mortal condition which necessitates it shall pass away.” (Book XIX, Chapter 17)

The Two Kingdoms

According to reformers like Martin Luther, God has ordained two kingdoms:

- The Spiritual Kingdom: This is the church’s domain. It governs matters of faith, salvation, and moral conduct. Its authority comes from God’s Word and is exercised through preaching, teaching, and the sacraments.

- The Temporal Kingdom: This is the government’s realm. It handles civil order, justice, and societal well-being. Its authority comes from God as well, but it wields the sword to maintain peace and punish wrongdoing.

Here’s how Luther described it:

“God has ordained two governments: the spiritual, by which the Holy Spirit produces Christians and righteous people under Christ; and the temporal, which restrains the un-Christian and wicked so that—no thanks to them—they are obliged to keep still and maintain outward peace.”

Two different tools, two different jobs, but both working under God’s authority.

Calvin likewise would write:

"...there is a twofold government in man: one aspect is spiritual, whereby the conscience is instructed in piety and in reverencing God; the second is political, whereby man is educated for the duties of humanity and citizenship that must be maintained among men. These are usually called the “spiritual” and the “temporal” jurisdictions..." (Calvin's Institutes III.xix.15)

Magisterial Reformers and Two Kingdoms

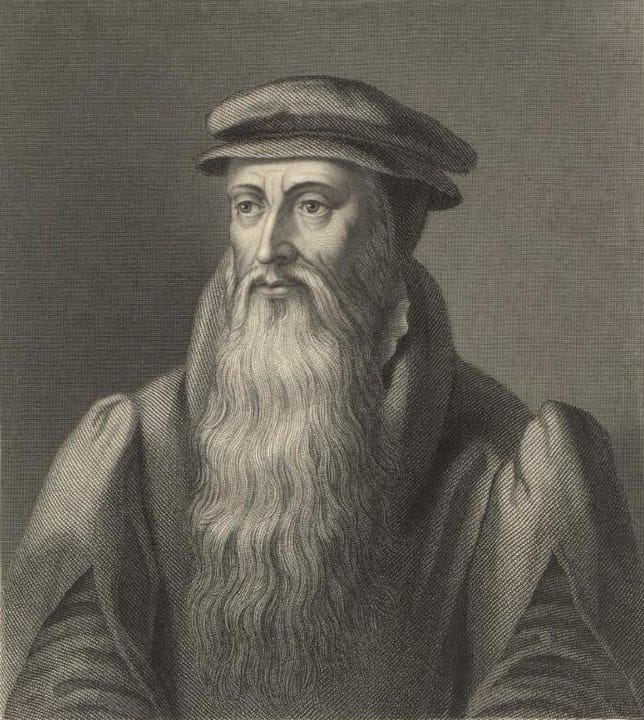

This wasn’t just a theory. Luther, John Calvin, and Ulrich Zwingli prayed for and sought to see this put into practice. They worked with governments to promote godliness and order, but they maintained that the church and state had distinct roles.

Martin Luther, John Calvin, John Knox

- Luther in Germany: Luther partnered with German princes to protect the Reformation. But he also insisted that civil rulers had no authority over the Word of God.

- Calvin in Geneva: Calvin’s model was similar. The church elders governed spiritual matters, while the civil magistrates handled temporal ones. Calvin’s Ecclesiastical Ordinances spelled out that the church had authority over excommunication, not the state.

- John Knox in Scotland: Knox took this even further, advocating for a Presbyterian system where church elders had significant authority, independent of the crown.

Why This Was Revolutionary

This was a huge shift from what came before. Under the medieval model, the pope could tell kings what to do, and kings could meddle in church affairs. But the Reformers sought to have the two distinct yet working together.

They weren’t advocating for a full separation of church and state. Instead, they argued for cooperation, with each respecting the other’s God-given role.

What Happens When This Goes Wrong?

Here’s where it gets tricky. When the balance is off, you get chaos. If the state starts running the church, you’re back to Henry VIII running the church like Constantine of old. If the church tries to run the state, you’re back to medieval popes crowning and deposing kings.

The Reformers understood this tension. They knew the two kingdoms needed to work together, but they also knew the dangers of one kingdom overstepping its bounds.

This view was held in America by the colonists and leading theologians of that time: John Winthrop, William Bradford, John Cotton, Cotton Mather, and Jonathan Edwards. This was why most of the American colonies had an established church.

This was the old two kingdoms view espoused in the RPCNA's ordination vows. The Erastianism of the king trying to rule the church was wrong. But so is the idea of the church wielding the sword. Two kingdoms, differing roles, differing tools, overlapping goals at times, both with Jesus reigning supreme over them.

Radical Church State Separation

The Reformers saw value in church and state working together within their separate spheres. But the Anabaptists went further. They believed any alliance with the state compromised the church’s purity. For them, total separation was essential to live faithfully under Christ’s rule.

This was something completely different: Radical Church-State Separation. This view was championed by the Anabaptists during the Reformation. While the Magisterial Reformers like Luther and Calvin believed in collaboration between church and state, the Anabaptists said, “Nope. These two have to stay as far apart as possible.” This was two kingdoms theology taken to a much further end.

The Core Belief: Total Separation

For the Anabaptists, the state was not just a separate realm—it was inherently worldly and corrupt. They believed that any connection between the church and the state would compromise the purity of the church. In their eyes, the church should be a community of true believers, separate from the institutions of the world.

Here's how Calvin described this view:

"...this distinction [between church and state] does not lead us to consider the whole nature of government a thing polluted, which has nothing to do with Christian men. That is what, indeed, certain fanatics who delight in unbridled license shout and boast: after we have died through Christ to the elements of this world [Col. 2:20], are transported to God’s Kingdom, and sit among heavenly beings, it is a thing unworthy of us and set far beneath our excellence to be occupied with those vile and worldly cares which have to do with business foreign to a Christian man. To what purpose, they ask, are there laws without trials and tribunals? But what has a Christian man to do with trials themselves? Indeed, if it is not lawful to kill, why do we have laws and trials?" (Calvin's Institutes IV.xx.2)

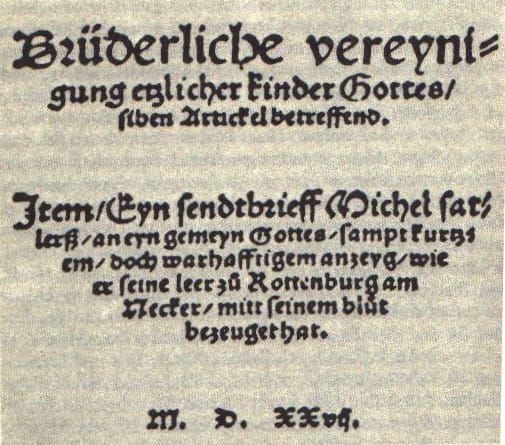

In the Schleitheim Confession of Faith in 1527, the Anabaptists didn’t just tweak the relationship between church and state; they turned it on its head. For the Anabaptists, the key was radical separation.

Separation of Church and State

The Anabaptists believed the state operates by the sword. This is done through force, coercion, and violence. In contrast, the church wields spiritual tools: the Word of God, faith, and church discipline (excommunication, often called “the ban”). For them, these realms were fundamentally incompatible. They were oil and water, never to be fully mixed. And indeed, will always separate.

Christians were called to live in obedience to Christ, not Caesar. These separatists would not serve as magistrates, judges, or any civic role because it would require the use of coercion. In their minds, Jesus himself rejected earthly kingship and refused to act as a judge in worldly disputes. Jesus was the model, and God’s kingdom is not of this world.

Pacifism

The Anabaptists were absolute pacifists. They believed Christians were called to a life of nonviolence, no matter the circumstance. Defending your family? Nope. Fighting for your country? Definitely not.

They took Jesus’ words "turn the other cheek" and "resist no evil" literally. Violence was the tool of the state, not the church or any individual in the church. The sword was given by God to secular rulers to maintain order in a fallen world. But Christ’s followers were called to overcome evil with good, not by force.

Two Kingdoms Divided

The Anabaptists divided the world into two kingdoms:

- The Kingdom of the World: Governed by human authorities, marked by sin, violence, and coercion.

- The Kingdom of God: Composed of believers living under Christ’s rule, striving for holiness, and awaiting their heavenly citizenship.

They saw these two kingdoms as completely incompatible. For them, Christians shouldn’t participate in the kingdom of the world at all. No holding public office, no serving in the military. There could be no dual citizenship. They were citizens of heaven, and their allegiance was solely to the Kingdom of God.

Call to Holiness and Separation

This didn’t just stop at avoiding civic duties. The confession mandated that Christians should separate from anything that could corrupt their witness. To them, the world was “Babylon,” and believers were called to come out and be separate.

This meant avoiding state functions like military service and political office. They refused to do anything that could be seen as unbiblical, including infant baptism and the state church system.

Their political theology and doctrine of sanctification were deeply intertwined. Separation from all things worldly was an attempt at maintaining purity and holiness and thus avoiding the judgment that would come upon the wicked.

Neutral Governance

The Enlightenment introduced a different solution to church and state tensions: neutral governance. Instead of choosing one religion, this model sought to create a level playing field where sects could coexist under a neutral state framework.

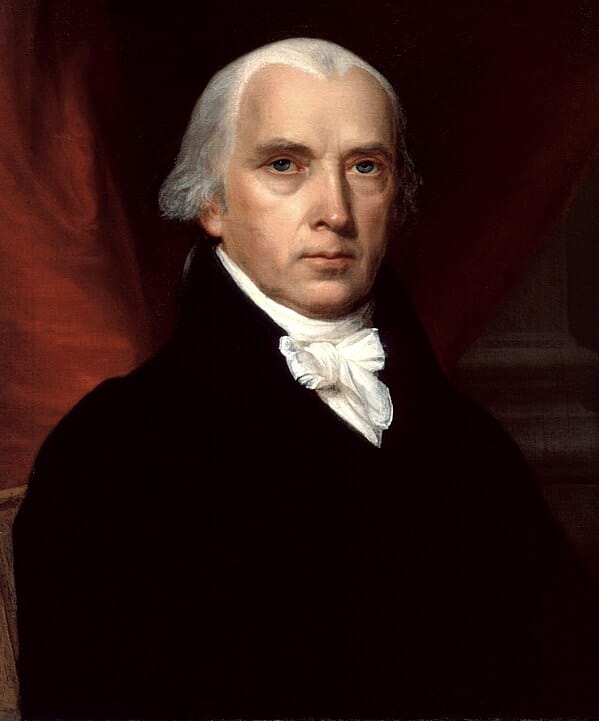

This was a significant development in the Enlightenment era and was particularly influenced by thinkers like John Locke in England. In America, this view was codified by James Madison as the principal author of the Bill of Rights.

The key principle is this: the government must neither endorse nor suppress any particular religion. Instead, it functions as a neutral arbiter, ensuring religious freedom for all without favoring any specific faith.

Madison wrote,

“The civil rights of none shall be abridged on account of religious belief or worship, nor shall any national religion be established, nor shall the full and equal rights of conscience be in any manner, or on any pretext, infringed.”

Historical Development

This model arose in response to centuries of religious conflict in Europe, as well as state-sponsored persecution of dissenters. The American experiment embodied this idea, with the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution explicitly prohibiting the establishment of a state religion while guaranteeing the free exercise of faith.

Under this system, the government doesn’t interfere in religious matters, nor does it allow religious bodies as institutions to wield state power. This was a balancing act aimed at preserving both religious liberty and social harmony.

This view is traditionally called "classical liberalism." It advocated for individual freedoms, limited government, and the protection of private property. The principle is that the state should protect basic rights: life, liberty, and property, without interfering in religious or personal matters.

From Civil Religion to Pluralistic Society

There was a gradual evolution of neutral governance that reflected a broader historical shift in societal identity. In its early phases, especially in the United States, the government operated within a framework of civil religion. There were broad Christian values that shaped public life. However, as societies became more religiously diverse, neutral governance evolved into outright pluralism.

Civil Religion in a Homogeneously “Christian” Society

In the early days of the American Republic, the concept of civil religion helped unify a population that was predominantly Christian, though divided by denominations. This wasn’t an official state religion, but rather a set of shared values and practices drawn from a general Christian ethos.

George Washington regularly emphasized the importance of religion and morality for the nation’s success. In his farewell address, he described these as “indispensable supports” for political prosperity. Abraham Lincoln, during the Civil War, often framed the conflict in biblical terms, seeing the nation’s struggles as part of a divine plan. At the 1896 Democratic Convention, William Jennings Bryan concluded his speech appealing to the common Christian identity: "You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns; you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold."

Public discourse, legal frameworks, and national rhetoric were deeply rooted in Christian moral principles and language. Political leaders often invoked God’s guidance. Religious references were common in public speeches and documents.

Practices like swearing oaths on the Bible, national days of prayer, and even in the 1950s, the phrase “In God We Trust” printed on U.S. currency reflected this consensus. These symbols reinforced the idea that America, while not formally a Christian nation, was deeply influenced by Christian beliefs.

The Transition to Pluralism

As immigration increased in the 19th and 20th centuries, the United States became more religiously diverse. The old civil religion model, based on a shared Christian moral foundation, began to give way to a more pluralistic society. This shift required the government to adapt its neutral stance to accommodate a wider array of beliefs.

Pluralism required expanding the interpretation of religious freedom to protect not only Christians but also Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, and non-religious individuals. Cases like Reynolds v. United States (1879) and Employment Division v. Smith (1990) tackled how far religious practices could be accommodated within the law.

Over time, symbols of other religions—menorahs, crescents, and even secular humanist icons—began appearing in public spaces alongside traditional Christian symbols. Yet, civil religion has remained predominantly Christian.

As society became more diverse, some lamented the loss of a unifying moral framework provided by civil religion. This sparked debates over expression in the public sphere. Should nativity scenes, menorahs, or even non-religious displays like Festivus poles be allowed on government property? Courts have wrestled with these questions, balancing free expression with the need for neutrality.

Lurking behind the shadows of neutrality and pluralism is always the call of secularism (but that's view #7). This often leads to conflicts when religious communities feel their voices are marginalized in the name of neutrality.

Two offshoots of Classical Liberalism

Out of classical liberalism would grow Libertarianism. This philosophy builds on classical liberalism but takes the principle of limited government further. Libertarians would argue that the state’s main or possibly only role is to protect individuals from coercion and violence. This individual liberty leaves people free to pursue their own moral and religious lives. The autonomous individual has the personal responsibility and the right to live according to their own convictions, as long as it doesn’t infringe on others’ rights.

Progressive liberalism shifts the focus toward equity and inclusivity. The progressive liberal aim is to protect marginalized groups and promote social justice. In this framework, neutral governance seeks to create a public square where all voices are heard, and no one is disadvantaged based on their sex, gender, orientation, beliefs, or practices.

Progressive liberalism stresses the need for active neutrality. The government takes steps to ensure religious and non-religious groups have equal opportunities to participate in public life. But not only does the government ensure all groups have equal opportunities, but the rights of minorities and their positions must be heard and not suppressed.

While classical liberalism focused on preventing government overreach, progressive liberalism seeks to actively level the playing field. This leads to debates about how far the state should go in accommodating diverse beliefs, lifestyles, and practices.

Both libertarians and progressive liberals would argue for the strict separation of church and state to preserve a pluralistic and free society.

Reformed Two Kingdoms Theology and Neutral Governance

Reformed theologians like D.G. Hart, Michael Horton, and David VanDrunen have drawn from these political philosophies to articulate a nuanced view of how Christians should engage with society under neutral governance.

Reformed Two Kingdoms Theology teaches that God governs the world through two distinct realms:

- The Civil Kingdom: Governed by human laws and institutions, tasked with maintaining justice, peace, and order. This is where neutral governance fits.

- The Spiritual Kingdom: Governed by Christ through the church, focusing on salvation, worship, and discipleship.

This distinction aligns with classical liberalism’s emphasis on limited government. The civil kingdom shouldn’t enforce religious practices. The spiritual kingdom shouldn’t wield political power.

D.G. Hart, the skilled biographer of J. G. Machen (a libertarian himself), argues that the American experiment in religious liberty mirrors the Reformed understanding of the Two Kingdoms. For Hart, the best environment for the church to thrive is one where the state refrains from endorsing any particular religion. Hart argues this secular distinction allows the church to focus on its spiritual mission without being co-opted by political agendas.

Interestingly, Reformed Two Kingdoms Theology doesn’t align entirely with progressive liberalism, yet it does share a concern for ensuring that the state remains impartial, protecting the rights of all people. For example, VanDrunen highlights the importance of the state providing a just and equitable framework where Christians can live out their faith without fear of persecution, alongside others with different convictions.

Challenges and Implications

While neutral governance provided a framework for coexistence, it also created tensions. The state’s refusal to favor any particular religion led to debates over the role of faith in public life. Should religious symbols be displayed in government buildings? Can public schools lead prayers? These questions continue to test the limits of neutrality.

Moral Influence Model

Religion Guides the State’s Conscience

While neutral governance kept the government from favoring a particular religion, many still believed moral values rooted in Christianity should guide public life. Leaders like Billy Graham became examples of this model, advocating for biblical principles to influence societal norms and laws without establishing a state religion.

The Moral Influence Model assumes that religion, particularly Christianity, serves as a vital guide for public morality. This is the idea that the state should never have an established church, and yet there is a war of ideas. The soul of the people must be won, including governors and civil authorities. And if civil authorities are Christian, then they should advocate for Christianly influenced moral principles and policies.

This model doesn’t seek to merge church and state but believes that religious values should shape laws and societal norms. Historically, it’s played out in pivotal moments, championed by key figures, and enshrined in significant theological documents.

The 2nd London Baptist Confession, Chapter 24

One of the clearest theological articulations of this model comes from the 2nd London Baptist Confession of Faith (1689). While the confession affirms the distinct roles of church and state, it also emphasizes that civil authorities are accountable to God.

Here’s the principles it espouses:

- God-Ordained Authority: Civil magistrates are appointed by God to maintain justice and peace.

- Promoting Good, Punishing Evil: The government’s role is to uphold righteousness and suppress wickedness, based on moral principles that align with God’s law.

- Christian Influence: The confession does not advocate for a theocracy. Rather, it acknowledges that Christian values should guide rulers in fulfilling their duties.

Evangelical Figures and the Moral Influence Model

If we fast forward to the 20th century, you’ll find this model prominently embodied in the work of evangelical leaders like Billy Graham. Graham wasn’t a politician, but his influence on American public life was immense.

Through his massive evangelistic crusades, Graham called individuals and nations to repentance. He frequently met with presidents, from Eisenhower to Clinton, offering spiritual counsel and urging them to govern with integrity and moral clarity. He had no hesitation staying as a guest in the White House or meeting with Queen Elizabeth.

Graham avoided partisan politics, but he didn’t shy away from advocating for policies he believed aligned with biblical principles. He used his influence for racial reconciliation and peace efforts during the Cold War.

Graham’s approach highlights a key aspect of the Moral Influence Model. Christians can shape society by influencing its leaders and calling the nation back to moral foundations without directly wielding political power.

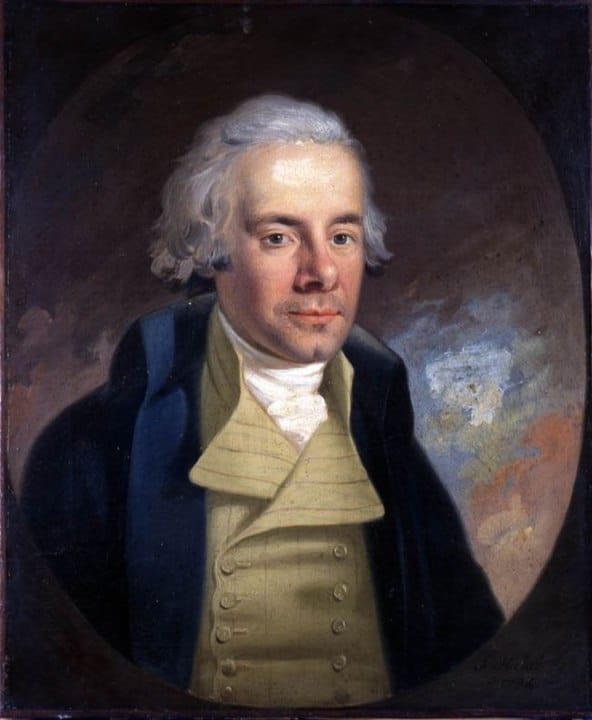

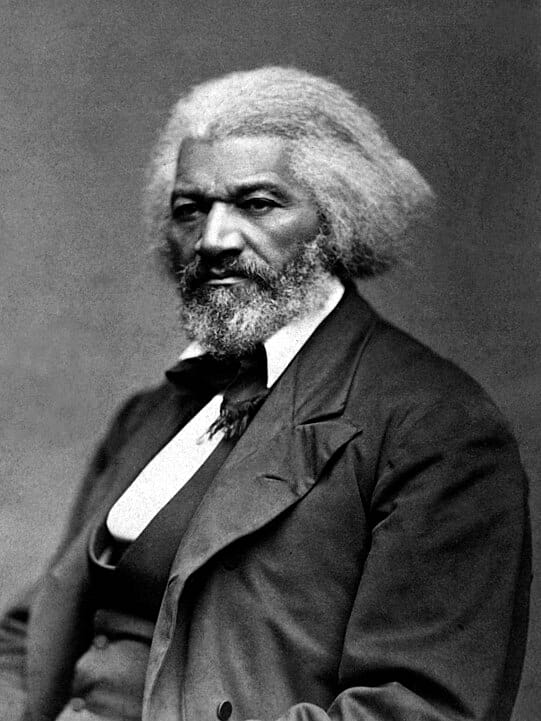

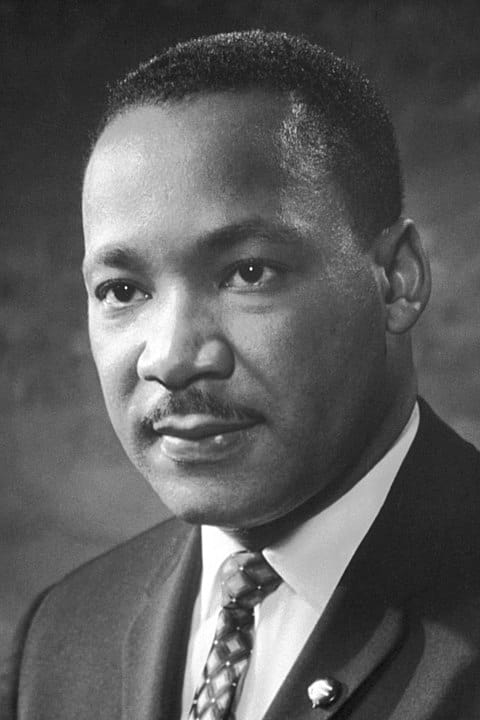

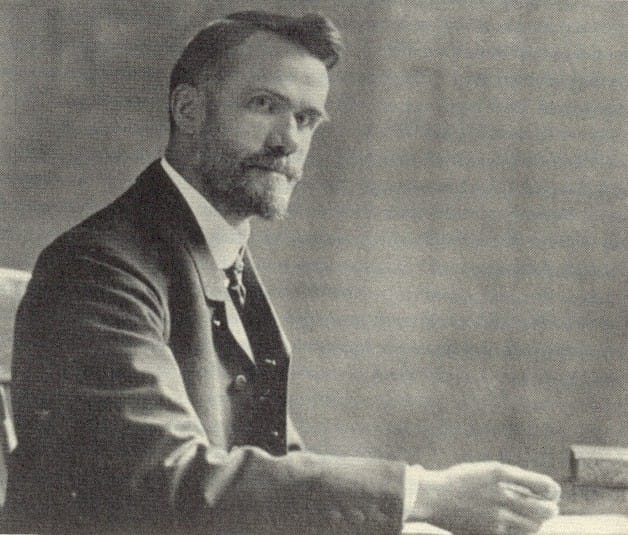

William Wilberforce, Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King Jr., and Walter Rauschenbusch - Public Domain

Graham is just one example in a long line of this political theology. William Wilberforce in England and Frederick Douglass in the U.S. relied on Christian moral arguments to fight against the institution of slavery. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. drew from the teachings of Scripture and pushed for societal change through nonviolent protest, framing racial justice as a moral imperative. And even social gospel leaders like Walter Rauschenbusch sought to address systemic injustices through policies rooted in Christian ethics.

Balancing Influence and Pluralism

The Moral Influence Model walks a fine line. It calls for Christian values to shape public life but doesn’t push for religious coercion or establishment. This balance is especially palpable in pluralistic societies, where multiple belief systems compete in the public square. It is not too much of a stretch to say this is the predominant view amongst evangelicals of today.

Secular Suppression

In some contexts, neutrality was not an option. Rather, the only way forward was hostility. Secular suppression emerged when religion began to be seen not as a partner in moral guidance but as an obstacle to progress, liberty, equality, happiness, and national unity. Revolutionary and totalitarian regimes sought to remove religious influence altogether, often with devastating consequences.

To understand the secular suppression model, we must explore its historical, theological, and political development. We'll trace its roots from the French Revolution through the rise of communist regimes.

The French Revolution: Religion as the Enemy of Liberty

The French Revolution (1789–1799) was a pivotal moment in the history of secular suppression. By the late 18th century, the Catholic Church was deeply intertwined with the French monarchy. It held immense wealth, political power, and social influence, often at the expense of the common people. The revolutionary leaders viewed the church not as a spiritual institution, but as an extension of the oppressive regime.

Portrait c. 1720s of Voltair, the Musée Carnavalet and Louis-Michel van Loo: Portrait of Denis Diderot (1767). Louvre. - Public Domain

Voltaire’s famous cry to “crush the infamy” was directed squarely at the church. He once wrote:

"Every sensible man, every honorable man must hold the Christian religion in horror."

His contemporary Diderot, a known atheist and editor of the encyclopedia, wrote:

“Man will never be free until the last king is strangled with the entrails of the last priest.”

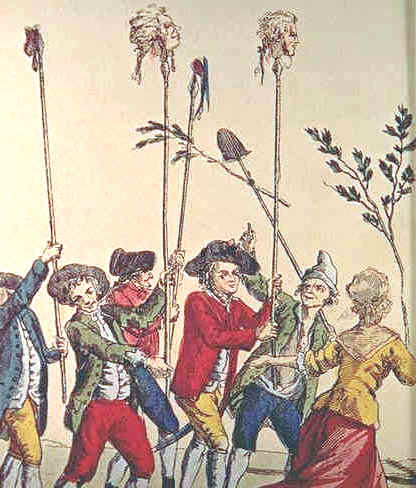

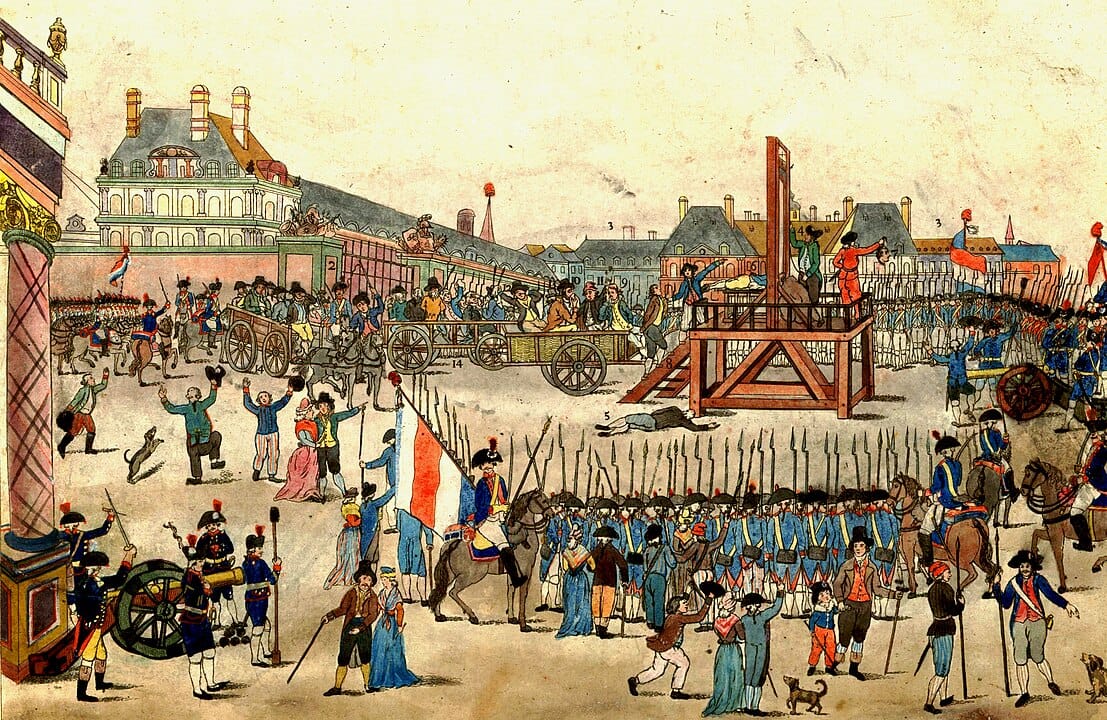

In response, the revolutionaries launched a campaign to strip France not only of its monarchy but of its religious identity. Churches were closed, priests were exiled or executed, and Christian symbols were removed from public spaces. The Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris was repurposed into the Temple of Reason.

The mass was out, and the Cult of Reason reigned. The Triune God of the Scriptures was jettisoned for the Cult of the Supreme Being. New civic religions were designed to replace Christianity. Rationality, liberty, and the sovereignty of human reason were to reign supreme. While short-lived, they symbolized the revolution’s attempt to construct a society devoid of traditional religious structures. Dechristianization during the Reign of Terror was a bloody affair. Religious communities were violently suppressed. The revolutionaries believed that dismantling the church was essential to creating a free and egalitarian society.

Portrait of Robespierre, Aristocrats' Heads on Pikes, and the Execution of Robespierre

Robespierre, with his Reign of Terror, would eventually be overthrown and executed. There was a shift from radical revolutionary fervor to a more moderate and conservative approach. Yet, factions arose desperately trying to fill the vacuum left by the fall of the monarchy. The government was weak and ineffective. The economic situation remained dire. Inflation, unemployment, and social unrest were rampant. The government struggled to address these issues, further weakening its legitimacy.

Meanwhile, Napoleon was on the rise as a military commander and was gaining fame and popularity through his victories in the French Revolutionary Wars. Napoleon became a symbol of French pride and offered hope for a strong and stable government. And in 1799, he seized power and eventually crowned himself Emperor of France. It was no pope who put the crown on Napoleon's head, but he crowned himself. The era of the individual sovereign had arrived.

Marxist Ideology: Religion as the Opium of the People

Portrait of Karl Marx (1818–1883) By John Jabez Edwin Mayall. Standing portrait of Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924), Marxist revolutionary and leader of Soviet Russia and the Soviet Union from 1917 to 1924. And A cropped image of Joseph Stalin during the Tehran Conference. Mao Zedong 1963. Portrait of Pol Pot Public Domain,

The seeds of secular suppression planted during the French Revolution found new life in the 19th century, particularly through the works of Karl Marx. Marx famously described religion as the “opium of the people,” a comforting illusion that numbed the pain of oppression while keeping the working class subservient to the ruling elite. Marx wrote:

"The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions. The criticism of religion is, therefore, in embryo, the criticism of that vale of tears of which religion is the halo."

For Marx, religion wasn’t just a personal delusion. Religion was a structural and systemic problem. All religion justified social hierarchies and distracted people from the material realities of economic exploitation. Religion was at best an ignorant placebo to the people's real suffering or at worst an enemy of the people, and they conspired to suppress the people.

The Soviet Union under Lenin and Stalin adopted Marx's philosophy. They saw the church as a competing power structure that needed to be dismantled for the proletariat to achieve true liberation.

Throughout the 20th century, communist governments implemented policies of secular suppression on a massive scale. Religion is an enemy to the people and thus to the state. These regimes didn’t just marginalize religion—they sought to eradicate it altogether.

After the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the Soviet government seized church property, outlawed religious education, and persecuted clergy. The Russian Orthodox Church, once a powerful institution, was decimated. By the time of Stalin’s purges, thousands of churches had been destroyed, and countless priests and believers were executed or sent to labor camps.

As the political theology went to China, it took an equally dark hold. Under Mao Zedong, the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) targeted all religious institutions as relics of the feudal or colonial past. Churches, temples, and mosques were destroyed. Religious leaders were publicly humiliated and imprisoned. The aim was to replace traditional beliefs with loyalty to the Communist Party and its ideology.

In Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot, went even further. Their radical attempt to create an atheist, agrarian utopia led to the mass slaughter of religious leaders and the destruction of religious sites. The regime sought to erase all traces of religion from Cambodian society.

Secular suppression represents an extreme form of rebellion against the Lordship of Christ. In these regimes, the state seeks to replace God as the ultimate authority. The government demands absolute loyalty and suppresses any competing allegiance.

The state under communism will not tolerate another kingdom. It is by its nature a totalitarian philosophy and becomes its own idol. Secular suppression elevates the state to the level of a deity and demands total devotion from its citizens. This demand is enforced with cruel force. One estimate is that over 94 million people died or were killed under communist regimes in the twentieth century.

Not all secular societies are so ideologically driven to the destruction of religion outright. Rather, many Western secular societies today marginalize religion not through violence, but by relegating it to the private sphere. Desires to express oneself religiously in the public square, especially from a Christian or biblical perspective, are deemed offensive and possibly a violation of others' civil rights.

Conclusion

this conclusion was edited on 11/14/2024 for clarity

Embracing the Historic Two Kingdoms

Throughout history, the relationship between church and state has swung between extremes. From state enforced religion to the church wielding political power, and from radical separation to outright suppression of faith. Amid these fluctuations, the Magisterial Reformation offers a balanced and biblically grounded model: the historic doctrine of Two Kingdoms. This doctrine provides a clear framework for understanding how Christ rules over both church and state as distinct yet complementary institutions.

Unlike some contemporary interpretations of Two Kingdoms theology, there should not be a wall of separation between the church and the state. Rather both, under Christ, should have a harmonious partnership where, though distinct in their roles, both could mutually support each other in promoting godliness and order. This partnership is rooted in the shared acknowledgment of Christ’s kingship. Both institutions support one another in fulfilling their God-ordained roles. Each institution serving in their respective complementary roles under His sovereign rule.

Christ’s Sovereign Rule

At the core of the Historic Two Kingdoms doctrine is the conviction that Christ is the mediatorial King over both realms. The Westminster Confession of Faith articulates this distinction:

"God, the supreme Lord and King of all the world, hath ordained civil magistrates, to be, under Him, over the people, for His own glory and the public good; and, to this end, hath armed them with the power of the sword, for the defence and encouragement of them that are good, and for the punishment of evildoers." (WCF 23.1)

In this model:

- The Temporal Kingdom: The state upholds justice, protects life and property, and maintains order. It exercises authority through the sword, ensuring societal stability.

- The Spiritual Kingdom: The church governs matters of faith, salvation, and moral conduct through the word and sacraments. It nurtures the spiritual wellbeing of believers.

While church and state wield different tools their goals overlap. Both seek to advance human flourishing under Christ’s reign. The church nurtures citizens with godly virtues, while the state ensures justice and peace. This creates a context in which the gospel can thrive.

Both kingdoms operate under Christ’s authority but focus on different aspects of human life. The state cannot legislate spiritual truths, and the church cannot enforce civil laws. But when both are aiming at the same goals God is glorified.

Contemporary "Reformed Two Kingdoms" perspectives can confine the church’s influence strictly to spiritual matters and even promote a secular state. The Historic Two Kingdoms model affirmed the church’s role in informing public life and conscience. The church’s proclamation of Biblical truth was seen as a guide for civil authorities, encouraging laws and policies that reflect God’s justice and righteousness.

The church retains a prophetic voice, calling civil authorities to uphold justice and righteousness according to God’s law. This responsibility ensures that the temporal kingdom does not stray from its divine mandate, even while it operates independently of ecclesiastical governance.

It should be noted that the Westminster Confession gave this reciprocity to the state as well to hold the church to account:

Yet [the civil magistrate] hath authority, and it is his duty, to take order, that unity and peace be preserved in the Church, that the truth of God be kept pure and entire; that all blasphemies and heresies be suppressed; all corruptions and abuses in worship and discipline prevented or reformed; and all the ordinances of God duly settled, administered and observed. For the better effecting whereof, he hath power to call synods, to be present at them, and to provide, that whatsoever is transacted in them be according to the mind of God. (WCF 23.5)

The RPCNA rejects this portion of the confession to protect against erastianism or state overreach in our non covenanted nation.

Avoiding Extremes

The Historic Two Kingdoms model effectively avoids the pitfalls of both Erastianism, where the state controls the church, and theocratic overreach, where the church dominates the state. By maintaining clear boundaries, each institution can function in its proper sphere while honoring their shared allegiance to Christ.

In the American context, this collaboration was evident in the establishment of churches and the integration of biblical principles into public policy. The civil religion taken for granted by both the "religious neutrality" and "religious influence" is a result of the historic two kingdoms model in the colonial era. The idea was not to enforce a theocracy in the colonies. Rather, it this model in Colonial America recognized that a well-ordered society benefited from the moral and spiritual guidance of the church. Natural law was extremely valuable. Natural law proves a ground work for civil justice. But, it is through special revelation that civil authorities can more fully align their governance with God’s righteousness. The Magisterial Reformers and Colonial leaders knew natural revelation wasn't enough to fully illuminate the path to becoming a great nation, a city on a hill.

Relevance Today

In today’s pluralistic society, the Historic Two Kingdoms doctrine remains highly relevant. It upholds the spiritual independence of the church, ensuring that worship and doctrine remain free from government overreach. While it simultaneously affirms the rightful authority of civil government to maintain order and promote the public good.

This balanced approach fosters cooperation between church and state. The reformation approach allows both to contribute to justice and human flourishing without overstepping their respective roles. While governments may falter in recognizing Christ’s rule nonetheless He is still sovereign and guides both realms toward their divine purposes.

A Call to Faithful Engagement

The Westminster Confession and Reformed Presbyterian Testimony provide a robust framework for Christians to engage with the world thoughtfully and faithfully. They encourage the church to remain steadfast in its spiritual mission while actively participating in civil life to promote justice and godliness.

In a world where pressures to either merge or completely separate church and state persist, the Historic Two Kingdoms doctrine offers a path of balanced engagement. It assures believers that Christ reigns supreme over all aspects of life, inspiring the church to fulfill its calling without compromising its spiritual integrity.

Final Affirmation

This balanced approach is why the courts of the RP Church are constituted and adjourned with the words, "In the name of Jesus Christ, Zion's only king and head." It serves as a constant reminder of Christ’s ultimate authority over both church and state.

Miscellaneous notes:

To give credit where credit is due the starting point for this post came from the Christ Over All article written by Andrew Nesalli. Though I used his material as a starting point this article is vastly different. When I presented this material in a sabbath afternoon I more closely followed Nesalli's models, nomenclature, slides, and even quoted him. You can find that presentation here: